Category: Agriculture

Erasing History? Budget Cuts Threaten to Gut Ag History at Iowa State University

Author Michael Crichton noted, “If you don’t know history, then you don’t know anything. You are a leaf that doesn’t know it is part of a tree.” Opportunities to preserve Iowa’s ag history are being uprooted, however, as Iowa State University’s (ISU) College of Liberal Arts and Sciences (LAS) plans to make millions of dollars in budget cuts.

ISU’s history department is among the hardest-hit departments. The latest budget cut, when combined with an earlier cut, will reduce the history department’s budget by 34% during the next three years. To meet this target, the history department is considering eliminating its graduate programs and search for further economies.

“The decisions made today influence the future,” said Michael M. Belding III, 31, a Ph.D. candidate studying rural, agricultural, technological, and environmental history at ISU. “I disagree with the budget cuts for ISU’s history department, because the people of Iowa deserve better.”

Belding has been gathering signatures to challenge these budget cuts, which would eliminate graduate programs in ISU’s history department.

Michael M. Belding III, a Ph.D. candidate studying rural, agricultural, technological, and environmental history at Iowa State University (ISU), has been gathering signatures to challenge severe budget cuts that would eliminate graduate programs in ISU’s history department.

He took action after Dr. Beate Schmittmann, LAS dean, announced a new round of budget cuts as part of her “Reimagining LAS” initiative. This is intended to “right-size” the budget in response to changing enrollment and student demand and “to position the college for future success,” according to ISU.

Slashing the history department’s budget will destroy ISU’s nationally-recognized RATE program, which focuses on rural history, agricultural history, technology history and environmental history. “If these proposed budget cuts occur, ISU is throwing away an innovative, important program,” noted Dr. Pamela Riney-Kehrberg, a distinguished professor of history at ISU.

If this happens, there will be long-lasting, negative impacts for Iowa, added Dr. Joe Anderson, a professor of history at Mount Royal University in Calgary, Alberta. “The Midwest has long been dynamic powerhouse of agriculture and innovation,” said Anderson, who earned his Ph.D. in history at ISU. “Everyone who cares about Iowa and its past should be mad as hell about ISU’s decision.”

Iowa’s ag heritage isn’t just for history majors

The risk of losing graduate programs in ISU’s history department doesn’t just affect future historians or professors. “This will limit opportunities to preserve Iowa’s cultural heritage,” said Dr. Kevin Mason, an assistant professor of history at Waldorf University in Forest City.

Not everyone who enrolls in history classes at ISU is a history major, added Mason, who received his Ph.D. in rural and environmental history from ISU in 2020. They include attorneys, engineers, architects and high school teachers who want to expand their knowledge of Iowa’s heritage. “If you care about Iowa history, you need to understand ag history.”

The only other university offering anything similar to ISU’s RATE program is Mississippi State University (MSU), although MSU focuses on Southern—not Midwestern—history. Neither the University of Iowa nor the University of Northern Iowa focus on ag/rural history, Riney-Kehrberg added.

“In most history courses and books, there’s little or no information on ag history following the Civil War,” noted Riney-Kehrberg, who researches American rural and agricultural history and will soon publish her latest book, When a Dream Dies: Agriculture, Iowa and the Farm Crisis of the 1980s. “The standard American history textbook might have one sentence about the Farm Crisis.”

The same dearth of information is evident when it comes to the role of women in agriculture. “There are many women’s studies courses today, but they often only teach the story of urban women, not rural women,” Riney-Kehrberg added.

“If these proposed budget cuts occur, ISU is throwing away an innovative, important program,” notes Dr. Pamela Riney-Kehrberg, a distinguished professor of history at Iowa State University.

History comes to life through the “land-grant land hunt”

While Yale University offers agrarian studies, it’s not the boots-on-the-ground style of research and extension that a land-grant university like ISU provides, Riney-Kehrberg noted.

Brandon Duxbury experienced this first-hand through the “land-grant land hunt” that ISU Extension undertook from 2014-2018. Contrary to popular belief, not a single acre of Story County land was given to Iowa State as part of the land-grant act (the Morrill Act) of 1862. Iowa was the first state to accept the provisions of the Morrill Act to build a college for the study of agriculture and the mechanical arts. Iowa Governor Samuel Kirkwood appointed Peter Melendy to select the best 210,000 acres of Iowa land to fund the new land-grant college. Most of this land was available in north-central and northwest Iowa.

Iowa became the first state to digitally map all these land-grant parcels within the state. Duxbury, a South Dakota native and graduate student in ISU’s history program, researched countless historical documents and interviewed current landowners to share their stories of their farmland. “People were always excited when we contacted them about this project,” said Duxbury, who is the new curator of collections at the Dacotah Prairie Museum in Aberdeen, South Dakota.

These stories, videos, a digital map and more can be found at www.landgrant.iastate.edu. “Efforts like this inspire people to ask better questions about the legacy they’re leaving with the land,” Duxbury said.

Making Iowa history relevant in ways like this is vital, said Belding, a Story City native who has links to his petitions on his Twitter account @mickey_belding. “I grew up thinking history involved big events that happened elsewhere, not here in Iowa. The more I research Iowa’s ag history, though, the more attached I get to Iowa.”

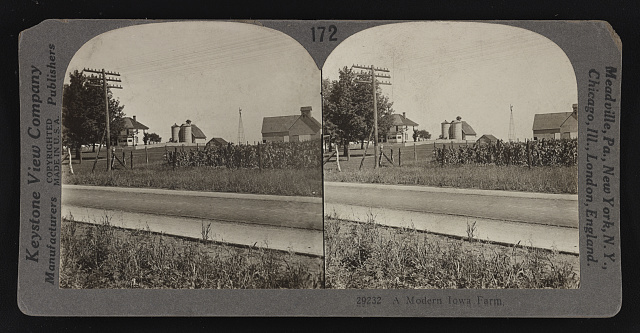

Family farms like this one near Yetter in Calhoun County have driven the economy in Iowa and the Midwest for generations. “The Midwest has long been dynamic powerhouse of agriculture and innovation,” says Dr. Joe Anderson, a professor of history at Mount Royal University in Calgary, Alberta, who earned his Ph.D. in history at Iowa State University (ISU). “Everyone who cares about Iowa and its past should be mad as hell about ISU’s decision.”

Teaching history prepares students for success

Along with researching and preserving Iowa history, ISU’s history department helps students develop a broad skill set, including communication. “My dad was a computer programmer who was promoted to management,” Riney-Kehrberg said. “He always emphasized that reading, writing and speaking skills were essential for a successful career.”

History classes also teach students research skills, data analysis and critical thinking. “You have to make an argument, and then find facts to support this argument,” Riney-Kehrberg said. “All this requires you to think carefully and broadly.”

Studies show that students with a solid LAS education, including history, have some of the best outcomes five years after college graduation. “These graduates tend to make more money, are the least likely to be fired, are less likely to move back home to live with their parents and are more likely to be promoted,” said Anderson, citing sources like the 2018 report “Humans Wanted: The Coming Skills Revolution,” published by the Royal Bank of Canada. “We’re very short-sighted as a culture if we devalue skills that come from studying the humanities.”

The “soft skills” of how people communicate with each other, interact with colleagues and solve problems are just as important to workplace readiness and employability as hard skills, especially as technology evolves. “It doesn’t take a ‘George Jetson’ moment to imagine a day when artificial intelligence and other technologies will replace some of the jobs we currently train people for,” Anderson, who served as director of history and interpretation at Living History Farms in Urbandale in the 1990s. “Our society will always need people who are skilled in human connection and communication.”

Society also needs educated citizens, both rural and urban, with a solid understanding of agricultural history, Anderson added. “People who are trained in ISU’s history department often go on to run museums in Iowa and the Midwest, teach at community colleges like DMACC or Hawkeye Community College, teach at land-grant universities, or pursue a variety of other careers.”

Everywhere they go, these professionals take Iowa history with them, noted Anderson, a south-central Nebraska native who loved spending time on his grandparents’ farms in Missouri and Iowa. He often incorporates Midwestern history into the classes he teaches in Canada. “This perspective helps people better understand many pressing issues today, from water quality to food production.”

Integrating history with tourism, economic development

It’s essential to be open to new ways of making Iowa history relevant to a wider audience, Mason said. “I believe history departments, especially at a land-grant like ISU, can collaborate across academic disciplines to help create a more diversified economy that encourages young people to stay in Iowa.”

Mason, who grew up in Pella, saw how Iowa history was intertwined with job creation, economic development and tourism in his hometown. “Tradition is important in Pella. Honoring this heritage helps young people gain a sense of place and the sense of pride that comes from knowing their history.”

Anyone who is concerned about the proposed funding cuts to ISU’s history department should contact their state legislators, the Board of Regents, and Dr. Beate Schmittmann, dean of the College of LAS at ISU. It’s important to take action now, Duxbury said. “The loss of ISU’s graduate history programs is a loss to Iowa history. Fighting these drastic cuts is a battle worth fighting.”

Note: I wrote this article for Farm News. It first appeared in the Friday, May 27, 2022, edition of Farm News. I’ve had a number of people ask me what they can do to fight these budget cuts. First, if you’re an Iowan, contact the senator and representative who represent you at the state level in the Iowa legislature. Also, contact leaders at ISU, including:

Iowa State University

Attn. Dr. Beate Schmittmann

202 Catt

2224 Osborn Dr.

Ames IA 50011-4009

Iowa State University

Office of the President, Dr. Wendy Wintersteen

515 Morrill Road

1750 Beardshear Hall

Ames, IA 50011

Want more?

I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you value intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, agriculture updates, recipes and tips to make you a better communicator.

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press. Also take a look at my other books, including “Iowa Agriculture: A History of Farming, Family and Food” from The History Press, “Madison County,” “Dallas County” and “Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing. All are filled with vintage photos and compelling stories that showcase the history of small-town and rural Iowa. Click here to order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page, or click here. Feel free to share this with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

Also, if you or someone you know could use my writing services (I’m not only Iowa’s storyteller, but a professionally-trained journalist with 20 years of experience), let’s talk. I work with businesses and organizations within Iowa and across the country to unleash the power of great storytelling to define their brand and connect with their audience through clear, compelling blog posts, articles, news releases, feature stories, newsletter articles, social media, video scripts, and photography. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com, or e-mail me at yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com, and yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Talk to you soon!

Machines that Changed America: John Froelich Invents the First Tractor in Iowa

Today, it’s hard to imagine a cornfield without a tractor in the picture. I was thinking about tractor history when The History Channel featured “The Machines That Built America.” I was glad to see they included the story of John Froelich, which I featured in my 2020 book Iowa Agriculture: A History of Farming, Family and Food.

Here’s an excerpt:

Back in 1892 in the tiny village of Froelich in Clayton County, Iowa, however, folks were amused by what a local businessman, John Froelich, was saying.

This northeast Iowa entrepreneur (1849 -1933) believed that mechanical power had a great future—that someday traction engines would do the work of horses even on mid-sized and large farms. The locals had to admit, though, that Froelich had invented several handy gadgets, including a more efficient washing machine, plus he was a good businessman.

Froelich ran a grain elevator, plus he ran a well-digging business and operated a threshing rig. Every year he took a crew of men to Langford, South Dakota, to work the fields. Froelich had considerable experience with steam engines and knew their pitfalls. They were heavy and bulky. They were hard to maneuver. They were always threatening to set fire to the grain and stubble fields. On the flat prairie, with a strong wind blowing, that was no joke.

A frustrated Froelich decided he could invent a better way to power the engine. The solution was gasoline. Froelich and local blacksmith Will Mann came up a vertical, one-cylinder engine mounted on the running gear of a steam traction engine – a hybrid of their own making. They designed many new parts to make it all fit together, but it finally was done. The word “tractor” wasn’t used in those days, but that’s what Froelich invented.

A few weeks later Froelich and his crew started for the broad fields of South Dakota with the “tractor” and a new threshing machine. That fall they threshed 72,000 bushels of small grain. It was a success!

Later that fall, Froelich shipped his “tractor” to Waterloo, Iowa, to show some businessmen. Immediately, the men formed a company to manufacture the “Froelich Tractor.” They named the company The Waterloo Gasoline Traction Engine Company and made Froelich the president.

Unfortunately, efforts to sell the practical, gasoline-powered tractor failed. Two were sold and shortly returned. The company then decided to manufacture stationary gas engines to provide income while tractor experiments continued, according to the Froelich Museum.

In 1895, the Waterloo Gasoline Engine Company was incorporated, but Froelich, whose interest was in tractors, not stationary engines, chose to withdraw from the company. The Waterloo Company continued to build stationary engines while trying to improve the tractor. In 1913 the model “L-A” was made.

In 1914, the first Waterloo Boy tractor, the Model “R” single-speed tractor, was introduced. Farmers liked it, and sales reached 118 within a year. When the Model “N” Waterloo Boy with two forward speeds was introduced, it was also successful.

When World War I led to rising farm prices and strong demand for dependable mechanical farm power, the concept of the tractor became so popular many tractor manufacturers sprung up in a matter of months. Deere and Company in Moline, Illinois, which manufactured a full line of John Deere implements, had been watching the progress of the Waterloo Engine Company and the increasing quality of its products.

Deere was looking for an established farm tractor to round out its line, and the Waterloo Engine Company fit the bill. Today, Deere’s facility in Waterloo remains one of the largest tractor-producing plants in the nation.

Tractors of various types and sizes that make farming easier and more efficient are shipped to farmers all over the world. For this contribution, John Froelich will long be remembered, and the village of Froelich, Iowa, remains “Tractor Town U.S.A.”

Tractor enthusiasts from around the globe travel to this tiny village to visit the birthplace of the tractor. At the 1891 general store, guests can view a scale model of the first “Froelich Tractor” made from the original blueprints. Perhaps the monument erected in 1939 near the general store best captures the essence of this unique place.

“In this village, John Froelich built the first gasoline tractor that propelled itself backwards as well as forward. Far-reaching in its effect on modern agricultural history, it moved out of this village and into the world in 1892. Later that year, Mr. Froelich joined with others in organizing the Waterloo Gasoline Traction Engine Company, which later became the John Deere Tractor Company.”

Meeting the challenge of a reliable, durable tractor

This history took center stage at the 2018 Iowa State Fair in Des Moines, when a butter sculpture of the Waterloo Boy Tractor stood next to the world-famous Butter Cow in the John Deere Agriculture Building’s 40-degree cooler throughout the fair, which ran from August 9-19.

To understand the significance of the Waterloo Boy, take a trip back in time, said Neil Dahlstrom, manager of the John Deere Archives and History. In the critical five-year stretch (1912-1917) prior to John Deere entering the tractor business, there were two key issues to address.

“First, what did farmers really want from a machine that would soon make the horse obsolete?” said Dahlstrom, who noted that salesmen, territory and branch managers, and Deere’s top leadership scoured the country to understand what customers desired. Also, how could the equipment to be manufactured to be durable enough to stand up to daily farm use?

Deere had considered every imaginable idea. The company had developed one-, two- and four-cylinder concept tractors. Some ran on gasoline. Others ran on kerosene. Some had all-wheel drive. Others had front-wheel drive. The company even explored concepts like line steering, which was meant to replicate horse reins as the steering mechanism to ease farmers into power farming, Dahlstrom said.

A motorized cultivator, what Deere called a “Tractivator,” was brought to market by several competitors, but Deere determined it did not provide any cost savings compared to horses.

The challenge of producing a durable tractor loomed large. In a letter to company president William Butterworth in 1915, Deere’s superintendent of factories George Mixter noted that tractors offered by competitors up to that point “have not been built with the proper spirit behind the design and manufacture to insure their durability in the hands of the farmers.” But if Deere could “build a small tractor that will really stand up for five or more years’ work on the farm, I believe they will be a permanent requirement of the American farmer,” Mixter wrote.

Deere ultimately found the solution with the Waterloo Boy tractor and acquired the Waterloo Gasoline Engine Company in Waterloo, Iowa, on March 14, 1918. Although anxious to start selling the Waterloo Boy, Deere dealers had to wait while Deere honored existing contracts, which did not expire until Dec. 31, 1918, Dahlstrom said.

Waterloo Boy makes its debut

Deere put its money where its instincts were. Over the next year, the company spent more than one-third of its advertising budget touting the Waterloo Boy tractor, Dahlstrom said.

Specifically, Deere invested $50,000 on tractor advertising in the year following its debut of the Waterloo Boy—approximately $747,000 in today’s money. Another way to get the company’s new product out in front of customers was to take it on the road – literally. The National Tractor Demonstrations started to become more mainstream after being introduced in the United States in 1913. An eight-city, eight-week tour schedule was the perfect opportunity to unveil Deere’s Waterloo Boy, Dahlstrom said. Salina, Kansas, served as the ideal backdrop in August 1918, since this was the nation’s largest demonstration.

The National Tractor Demonstrations started to become more mainstream after being introduced in the United States in 1913. An eight-city, eight-week tour schedule was the perfect opportunity to unveil Deere’s Waterloo Boy, Dahlstrom said. Salina, Kansas, served as the ideal backdrop in August 1918, since this was the nation’s largest demonstration.

Deere had participated in tractor demonstrations since the original Winnipeg Agricultural Motor Competitions in Manitoba, Canada, in 1908 – but not with a tractor. Instead, Deere had paired its plows with leading tractor manufacturers. That changed now that the Waterloo Boy was part of the Deere family.

At Salina, Deere spared no expense, showcasing 12 Waterloo Boy tractors as the centerpiece of a display that included John Deere signs, Waterloo Boy signs and a copper leaping deer statue, Dahlstrom said. “There were two stars during this week of 100-degree days – ‘ice water on tap’ and the Waterloo Boy Model ‘N’ tractor,” he added.

The Model “N” demonstrated its merits by pulling tractor plows, disc harrows and grain drills. Visitors were shuttled in three John Deere farm wagons pulled by Waterloo Boy tractors. By all accounts, the debut was a success.

“The award for the most elaborate, largest and most artistic exhibit tent at the Salina tractor show will undoubtedly go to the John Deere Plow company of Kansas City,” wrote the editors of a Kansas City newspaper.

As Deere’s advertising campaign swung into full gear, the Waterloo Boy tractor was promoted as the “best and most efficient tractor” on the market for farmers inclined to buy a tractor. By October 1918, readers of Deere’s magazine, The Furrow, saw an advertisement for the line of Waterloo Boy tractors and stationary engines. The ad guaranteed the Waterloo Boy’s “ample power for field and belt work.”

In January 1919, with tractors now available through John Deere dealers, Deere’s first print ad for the trade press appeared in The Farm Implement News. It featured two areas of emphasis: “A Good Tractor Backed by a Permanent Organization.”

After years of development, John Deere customers and John Deere dealers finally had their John Deere tractor. “It took longer than the company expected, but a determination to do it right instead of doing it fast now brought the John Deere tractor to market,” Dahlstrom said.

As a result, customers got “the assurance of more tractor work per dollar of fuel cost; longer tractor life with less repair cost; accessibility of parts that makes caring for the tractor simple and easy; and dependable power for all farm work.”

The tractor era had officially arrived, and Iowa found itself at the epicenter of this growing industry.

Want more?

I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you value intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, agriculture updates, recipes and tips to make you a better communicator.

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press. Also take a look at my other books, including “Iowa Agriculture: A History of Farming, Family and Food” from The History Press, “Madison County,” “Dallas County” and “Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing. All are filled with vintage photos and compelling stories that showcase the history of small-town and rural Iowa. Click here to order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page, or click here. Feel free to share this with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

Also, if you or someone you know could use my writing services (I’m not only Iowa’s storyteller, but a professionally-trained journalist with 20 years of experience), let’s talk. I work with businesses and organizations within Iowa and across the country to unleash the power of great storytelling to define their brand and connect with their audience through clear, compelling blog posts, articles, news releases, feature stories, newsletter articles, social media, video scripts, and photography. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com, or e-mail me at yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com, and yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Talk to you soon!

George Washington Carver Rose from Slavery to Ag Scientist

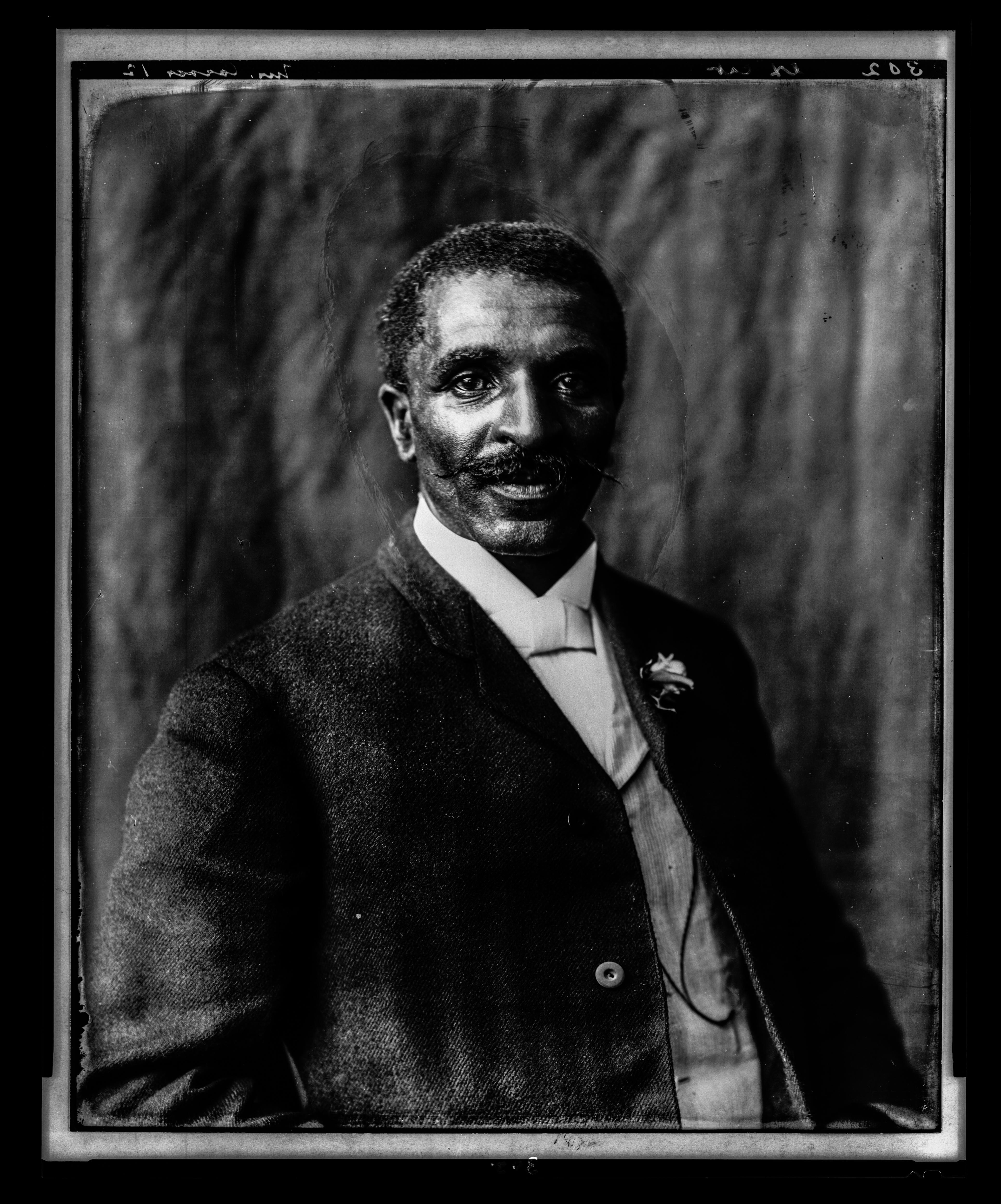

A man who was born a slave changed the world with his agricultural innovations, and the seeds for these contributions were planted in Iowa. When George Washington Carver was a student and faculty member at Iowa State, his research forever changed how farmers look at crop production.

While more than 120 years have passed since Carver completed his bachelor’s and master’s degrees at Iowa State in Ames, his spirit lives on.

Carver’s journey began on a southwest Missouri farm owned by Moses and Susan Carver near the town of Diamond. It’s uncertain whether Carver was born in 1864 or 1865. Both of his parents had been enslaved. His father died around the time of his birth. His mother, Mary, was given her freedom by the Carvers, and she adopted their last name.

The Carvers eventually took young George into their home and raised him as their own. He was unusually talented at almost everything he tried. By the time he was a teenager, Carver left the farm to attend a school for black children in Neosho, Missouri. For the next 10 years, Carver wandered from town to town in Missouri and Kansas in search of a better education. He supported himself by taking in laundry and doing household chores, according to. Iowa Pathways, an online learning environment from Iowa PBS.

“From a child, I had an inordinate desire for knowledge and especially music, painting, flowers, and the sciences, algebra being one of my favorite studies,” Carver wrote. “I wanted to know the name of every stone and flower and insect and bird and beast. I wanted to know where it got its color, where it got its life—but there was no one to tell me.”

Finding a new future, from Winterset to Ames

Carver was accepted at Highland College in Kansas, only to be turned away shortly after he arrived by school officials who were surprised by his skin color. Undeterred, he set off for Iowa, where he arrived in Winterset in 1888. This county seat town in Madison County was located along a section of the Underground Railroad that had been a hotbed of activity from 1857 through 1862, according to the Madison County Historic Preservation Commission.

While Carver found work as a hotel cook in Winterset, he wanted to be an artist—a painter—and capture the beauty of nature that so fascinated him. Friends in Winterset recognized his talents and encouraged him to enroll at Simpson College in Indianola, where he studied art and music. It took only a few months for his art teacher, Etta Budd, to realize that she had nothing else to teach the talented young man. At her urging, Carver transferred in 1891 to Iowa State College in Ames, where her father was the head of the Department of Horticulture.

Through quiet determination and perseverance, Carver excelled at his studies and became involved in all facets of campus life in Ames. He was an active participant in debating and agricultural societies and the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA). He was also a trainer for athletic teams (including Iowa State’s football team), captain of the campus military regiment and a dining room employee, according to Iowa State University (ISU). His poetry was published in the student newspaper, and his artwork was exhibited at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago.

Carver earned his bachelor’s degree in 1894. “Reading about nature is fine, but if a person walks in the woods and listens carefully, he can learn more than what is in books, for they speak with the voice of God,” Carver said. His professor, Dr. Louis Pammel, encouraged him to stay at Iowa State and pursue a graduate degree. Because of his proficiency in plant breeding, Caver was asked to join the faculty. Not only did he become the first black student at the school to earn a master’s degree (in 1896), but he also became Iowa State’s first black faculty member, all while expanding his knowledge and skills and writing professional papers of national acclaim.

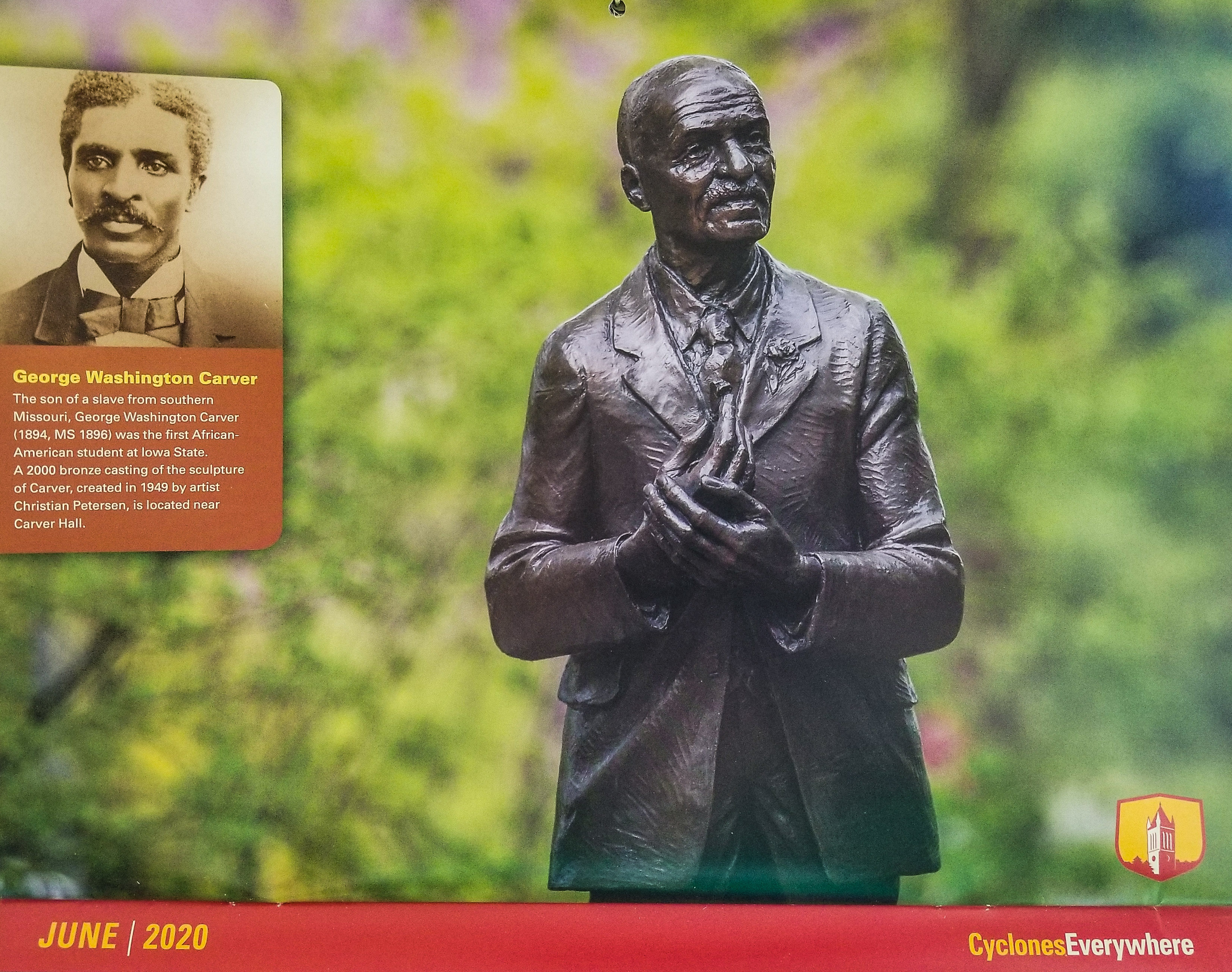

George Washington Carver on Iowa State University calendar

More opportunities take root

Carver planned to earn his doctorate at Iowa State, and the school wanted very much to keep him on its faculty. But then a letter arrived in 1896 that changed everything. “I cannot offer you money, position or fame,” it said. “The first two you have. The last, from the place you now occupy, you will no doubt achieve. These things I now ask you to give up. I offer you in their place work—hard, hard work—the task of bringing a people from degradation, poverty and waste to full manhood.” It was signed by Booker T. Washington, the principal of an industrial and teacher training institute for black students in Tuskegee, Alabama.

Washington was determined to make the Tuskegee Institute the leading black educational institution in the South. He wanted to establish an agriculture department. There were 5 million black farmers in the South. Most lived in poverty and ignorance of scientific agriculture. But to establish such a department, Washington knew that he needed a black man with an advanced degree in agriculture. There was only one such man in America: George Washington Carver.

Carver accepted Washington’s offer. This opportunity to serve fit with Carver’s philosophy that “education is the key to unlock the golden door of freedom.” Carver urged southern farmers to rotate crops and use organic fertilizers. He preached the value of planting soil-restoring crops such as peanuts, sweet potatoes and soybeans.

At Tuskegee, Carver gained an international reputation in research, teaching and outreach. His research resulted in the creation of more than 300 products from peanuts, more than 150 uses for sweet potatoes and multiple uses for soybeans. These products contributed to rural economic improvement by offering alternative crops to cotton that were beneficial for the farmers and the land.

“Anything will give up its secrets if you love it enough,” Carver wrote. “Not only have I found that when I talk to the little flower or to the little peanut they will give up their secrets, but I have found that when I silently commune with people, they give up their secrets also—if you love them enough.”

Some of Carver’s most interesting, plant-based innovations included diesel fuel, axle grease, hand cleaner, stains and paints, gasoline, glue, insecticide, linoleum, printer’s ink, plastics, laundry soap, medicines and more.

Service measures success

During World War I, Carver worked with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) as a consultant on food and nutrition. Carver had risen to fame nationwide by the 1920s and 1930s, thanks to his agricultural pursuits. By the early 1940s, Carver was working with Henry Ford, founder of Ford Motor Company, who supported the production of ethanol as an alternative fuel and showcased a car with a lightweight plastic body made from soybeans.

Carver remained at Tuskegee until his death in 1943. Landmarks across the nation have been named in honor of Carver, including the George Washington Carver Center on the U.S. Department of Agriculture campus in Beltsville, Maryland. In Iowa, Carver’s legacy is celebrated at Iowa State University, where Carver Hall was named in his honor. Through the George Washington Carver (GWC) Scholarship program, the university awards 100 scholarships in the amount of tuition to multicultural, first-year students coming to college directly out of high school.

All these tributes honor Carver, who devoted his life to education, research and community service to help others. “It is not the style of clothes one wears, neither the kind of automobile one drives, nor the amount of money one has in the bank, that counts,” Carver wrote. “These mean nothing. It is simply service that measures success.”

Want more?

This story is an excerpt from my book Iowa Agriculture: A History of Farming, Family and Food. Click here to learn more and order a signed copy here.

I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you value intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, agriculture updates, recipes and tips to make you a better communicator.

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press. Also take a look at my other books, including “Iowa Agriculture: A History of Farming, Family and Food” from The History Press, “Dallas County” and “Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing. All are filled with vintage photos and compelling stories that showcase the history of small-town and rural Iowa. Click here to order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page, or click here. Feel free to share this with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

Also, if you or someone you know could use my writing services (I’m not only Iowa’s storyteller, but a professionally-trained journalist with 20 years of experience), let’s talk. I work with businesses and organizations within Iowa and across the country to unleash the power of great storytelling to define their brand and connect with their audience through clear, compelling blog posts, articles, news releases, feature stories, newsletter articles, social media, video scripts, and photography. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com, or e-mail me at yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com, and yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Talk to you soon!

Myth Busting: No, Your Pork Doesn’t Come from China

There’s so much misinformation circulating on social media (and now I heard it on a radio program recently) that can be summarized as those “awful companies like Smithfield that raise pigs here in America but send them to China for processing before the meat is sent back to America to grocery stores–and then claim these are American products.” Aarrrgghh.

A caller to the talk show was irate about this, and the host agreed with her premise. Well, I’m not an expert in the meat industry, but I grew up on an Iowa hog farm, still live and work on an Iowa farm, worked in ag my entire career and know these things to be true:

1.) There’s a reason why new pork processing plants have been built in Iowa in recent years, like the new one near Eagle Grove. Iowa farmers raise a lot of pigs, and it makes economic and common sense to process the pigs close to where they are produced, rather than shipping them halfway around the world.

2.) Pigs that go to market weigh a lot (well over 200 pounds each, sometimes close to 300 pounds). Would it make any sense to ship them to China for processing and send the product back to America? Nope. Think how costly that would be.

I shared all this on a Facebook post the last week of April 2020 and was amazed when the post when viral within hours. Not only did the post garner 82 comments and 151 shares in less than a week, but it prompted many people to thank me for addressing this myth. I was pleased that my ag industry friends joined the conversation to combat fear with facts. One, a former executive with the National Pork Board, noted, “USDA has not approved China to ship pork to the U.S. In addition, China has lost half of their swine herd to African swine fever and is buying large amounts from anywhere they get their hands on it to address the shortage. They have no pork to export. End of story.”

Smtihfield Foods was founded in Smithfield, Virginia, in 1936 and was acquired by Hong Kong-based WH Group in 2013.

Smithfield has not, does not, and will not import any products from China to the United States. No Smithfield products come from animals raised, processed, or packaged in China. All our U.S. products are made in one of our nearly 50 facilities across America. These products are produced in compliance with the strict standards and regulations of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and other federal and state authorities.

WH Group is a publicly traded company with shareholders around the world. Anyone anywhere can purchase shares of WH Group on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange under the stock code 00288. In fact, WH Group’s shareholders include many large U.S.-based financial institutions. It is not a Chinese state-owned enterprise and does not undertake commercial activities on behalf of the Chinese government.

How has the acquisition impacted the U.S. pork industry and the country’s economy?

Smithfield and the U.S. pork industry export products to China, benefitting American pork producers and processors. More exports to China mean more American jobs and more demand for products “Made in the USA,” and reduces the U.S. global trade deficit.

The bottom line? Don’t worry. Your pork doesn’t come from China.

Want more?

I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you value intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, agriculture updates, recipes and tips to make you a better communicator.

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press. Also take a look at my other books, including “Iowa Agriculture: A History of Farming, Family and Food” from The History Press, “Dallas County” and “Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing. All are filled with vintage photos and compelling stories that showcase the history of small-town and rural Iowa. Click here to order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page, or click here. Feel free to share this with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

Also, if you or someone you know could use my writing services (I’m not only Iowa’s storyteller, but a professionally-trained journalist with 20 years of experience), let’s talk. I work with businesses and organizations within Iowa and across the country to unleash the power of great storytelling to define their brand and connect with their audience through clear, compelling blog posts, articles, news releases, feature stories, newsletter articles, social media, video scripts, and photography. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com, or e-mail me at yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com, and yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Talk to you soon!

Darcy

Sauce to Sanitizer: Cookies Food Products Bottles Hand Sanitizer Made with Ethanol

Going with the flow takes on a whole new meaning in times like this COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. It also explains why ethanol-based hand sanitizer has been flowing through the bottling line instead of barbecue sauce at Cookies Food Products Inc. in Wall Lake, Iowa.

“I’m a firm believer you have to pay rent for the space you occupy while you’re here on earth,” said Speed Herrig, who has grown Cookies Food Products into one of the largest regional sauce manufacturers in the country in the past 40 years. “We want to do what we can to help.”

That’s why Herrig didn’t hesitate to offer his company’s bottling resources when he heard that Southwest Iowa Renewable Energy (SIRE) near Council Bluffs was trying to fill bottles by hand with ethanol-based hand sanitizer they’d produced. Filling bottles manually from large plastic totes was complicated and slow, especially when time is of the essence to help protect people’s health.

Herrig knew there was a better way. Just as General Motors retooled some of its production lines to make ventilators during the COVID-19 pandemic, Cookies made some small modifications on its equipment so employees could fill jugs with hand sanitizer instead of barbecue sauce. The Cookies team filled 5,000 1-gallon jugs with hand sanitizer in a couple days in mid-April for SIRE. “We’re fortunate to have a lot of long-term, experienced employees at Cookies, so it wasn’t too hard to make these changes,” Herrig said.

Corn-based solutions fuel innovation

Corn-based solutions fuel innovation

By early April, hospitals and nursing homes in Iowa and beyond were desperately searching for hand sanitizer, as demand for the product soared. Ethanol plants that can make large batches of sanitizer’s main ingredient, alcohol, offered to help.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has stringent production standards designed to protect the quality of medicines, food ingredients and dietary supplements. Previously, the agency prohibited many ethanol plants from using their alcohol that didn’t meet high quality specifications for use in drugs or beverages.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, however, FDA revised its regulations, noted Justin Schultz, SIRE regulatory manager, who was quoted in the Council Bluffs Nonpareil newspaper several weeks ago. With the FDA’s new guidelines, ethanol made at plants that produce fuel ethanol can be used in a product like hand sanitizer, if the ethanol contains no additional additives or chemicals. Ethanol plants must also ensure water purity and proper sanitation of equipment.

SIRE produces more than 130 million gallons of fuel-grade ethanol per year and consumes more than 44.6 million bushels of corn annually. After FDA revised its guidelines this spring, SIRE shipped a few hundred gallons of pre-mixed hand sanitizer to Cookies’ Wall Lake bottling facility in early April. Once the Cookies team readjusted some settings to ensure the sanitizer would flow through their bottling system properly, they began filling 5,000 1-gallon plastic jugs.

The jugs of hand sanitizer were shipped to the Des Moines area to increase the state’s stockpile for distribution throughout Iowa. Herrig is glad that more people will be able to get the hand sanitizer they need, without being at the mercy of con artists.

“I’ve seen scammers selling hand sanitizer for well over twice the price it should be,” Herrig said. “Changing $75 a gallon or $10 for an 8-ounce bottle is outrageous. I don’t want to see anyone price gouging.”

Giving back

While Herrig added that the Cookies team played a small role in the fight against COVID-19, they viewed this as a way to help their fellow Iowans in a time of need.

“We’ve enjoyed doing business in Iowa for many years through our sauce business, our automotive parts business and our golf cart business,” said Herrig, who opened an automotive parts and repair business in 1962 on his family’s farm near Wall Lake. “Iowa has been a good place for me, and I want to give back.”

This article first appeared in the April 24, 2020, issue of Farm News.

Want more?

I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you value intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, agriculture updates, recipes and tips to make you a better communicator.

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press. Also take a look at my other books, including “Iowa Agriculture: A History of Farming, Family and Food” from The History Press, “Dallas County” and “Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing. All are filled with vintage photos and compelling stories that showcase the history of small-town and rural Iowa. Click here to order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page, or click here. Feel free to share this with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

Also, if you or someone you know could use my writing services (I’m not only Iowa’s storyteller, but a professionally-trained journalist with 20 years of experience), let’s talk. I work with businesses and organizations within Iowa and across the country to unleash the power of great storytelling to define their brand and connect with their audience through clear, compelling blog posts, articles, news releases, feature stories, newsletter articles, social media, video scripts, and photography. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com, or e-mail me at yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com, and yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Talk to you soon!

Darcy

When Agriculture Entered the Long Depression in the Early 1920s

The culture of Iowa agriculture hasn’t only been shaped by good times. The farm crisis that started in the 1920s, a decade before the Great Depression engulfed America, shook rural Iowa to its core. In the post–World War I era, the Golden Age of Agriculture was over, and farmers throughout the Midwest began to suffer the effects of an increasing economic depression that culminated at the close of the 1920s with the stock market crash.

“To understand the nature of the agricultural problem more clearly, it needs to be said that farming is a difficult and uncertain profession,” noted Gary D. Dixon in his thesis “Harrison County, Iowa: Aspects of Life from 1920 to 1930,” which he presented in 1997 to the Department of History to earn his Master of Arts degree from the University of Nebraska–Omaha. “The farmer has no control over the prices he pays for goods or, more importantly, for what he can ask for his own products, as he ‘buys in a seller’s market, and he sells in a buyer’s market.”

Wesells Living History Farm WW1

It was definitely a seller’s market during World War I, when all sectors of the American economy produced as much as possible to help the war effort. It was profitable, as well as patriotic, to raise crops at top capacity. But then the war ended on November 11, 1918.

“Government price supports for agriculture were kept through 1920, when the guaranteed prices on wheat and other crops were terminated,” Dixon noted. “The government ended loans to European nations at the same time, which meant they were unable to purchase U.S. agricultural products.”

This is what had kept the exports going, and exports had driven the boom in the U.S. farm economy. In the years just after World War I, prices for farm goods fell by half, as did farmer income. The Federal Reserve raised the credit rate just when the farmer needed its help the most, so money tightened up. Banks did not renew notes, but mortgages and bills still came due. To make it worse, the railroads raised their freight rates, so it was more expensive to get the crops to market, Dixon noted.

Farm income fell from $17.7 billion in 1919 to $10.5 million in 1921—nearly a 41 percent drop. In Iowa, farm values that had almost tripled between 1910 and 1920 plunged during the 1920s. In Harrison County in southwest Iowa, 1930 land values of $41 million reflected a drop of more than $35 million from 1920, Dixon said. In addition, Harrison County’s total crop values, which in 1919 were more than $10.8 million, fell to roughly $5.7 million by 1924. “Taxes on the remaining income, and the other expenses incurred in farming, remained as high as they ever were, or increased,” Dixon added.

While there had been a historic growth in the number and size of farms in the nation until 1920, that soon changed. Then the farm population showed net losses of 478,000 in 1922 and 234,000 in 1923. The more lucrative prospects of the city lured many of the best of the younger generations away, Dixon said.

Iowa farm, 1920s Source: Library of Congress

Banding Together in Farmer Cooperatives

In response to these troubling developments, some farmers began organizing with their neighbors so their shared concerns could be heard at the county, state and national level. Some turned to groups like the Iowa Farmers Union, which had formed in 1915 to help members work together to strengthen the independent family farm through education, legislation and cooperation.

Others turned to a new group, the Iowa Farm Bureau Federation (IFBF), which had formed on December 27, 1918, during a meeting in Marshalltown. The sSeventy-two county Farm Bureau groups from across Iowa voted unanimously during this meeting to form a state federation. These farmers knew that they needed a stronger voice in legislation governing their industry, improved marketing for their ag products and better relationships with other related industries, including meatpackers and the railroads.

“We regard this movement as one of the most sensible efforts toward an organization of farmers that has yet been made,” said Henry A. Wallace, the editor of Wallaces’ Farmer, who went on to become U.S. secretary of agriculture and vice president of the United States.

The IFBF also helped support the cooperative marketing movement that had been gaining momentum, noted Tim Neiss, IFBF historian. Ag cooperatives had started to form in Iowa by the mid-1800s in response to unfair business practices by the railroads that hurt competition and lowered the prices farmers received for their products. Farmers began banding together to market their products more efficiently, at higher prices, as well as to buy inputs at lower cost.

One of these early Iowa cooperatives was Farmers Cooperative Elevator of Marcus, which was incorporated on December 12, 1887. The Marcus location, which is now part of First Cooperative Association based in Cherokee, remains the oldest active cooperative elevator in the nation.

While organizing into farm organizations and cooperatives appealed to some farmers, other farmers decided to move in a much more radical direction—one of that would culminate in the Farmers Holiday movement and the near-lynching of an Iowa judge in Le Mars. Get the whole story in my book Iowa Agriculture: A History of Farming, Family and Food, which is published by The History Press the week of April 27, 2020.

Want more?

Thanks for stopping by. I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you value intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, agriculture updates, recipes and tips to make you a better

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press. Also take a look at my latest book, “Dallas County,” and my “Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing. Both are filled with vintage photos and compelling stories that showcase he history of small-town and rural Iowa. Order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page, or click here. Feel free to share this with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

Also, if you or someone you know could use my writing services (I’m not only Iowa’s storyteller, but a professionally-trained journalist with 20 years of experience), let’s talk. I work with businesses and organizations within Iowa and across the country to unleash the power of great storytelling to define their brand and connect with their audience through clear, compelling blog posts, articles, news releases, feature stories, newsletter articles, social media, video scripts, and photography. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com, or e-mail me at yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com, and yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Talk to you soon!

Darcy

Iowa’s “Peacemaker Pig” Floyd of Rosedale Helped Calm Racial Tensions

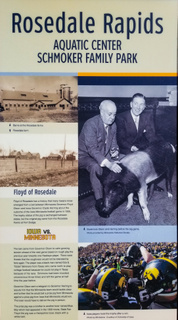

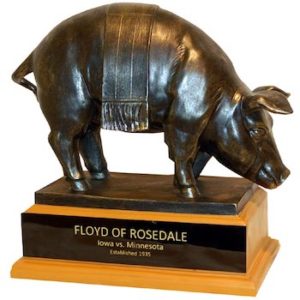

If you follow college football in the Midwest, especially if you’re a University of Iowa Hawkeye football fan, you may know the story of Floyd of Rosedale. A bronze statue of the pig, Floyd of Rosedale, is exchanged between the two states. The original pig himself came from Rosedale Farms at Fort Dodge in north-central Iowa.

The whole deal emerged from a bet between Iowa Governor Clyde Herring and Minnesota Governor Floyd Olson about the outcome of the 1935 Iowa-Minnesota football game, but this story involves something much deeper than a famous pig and a bronze trophy.

The problem started the previous year, on Saturday, October 27, 1934, when rough play was directed towards one Iowa Hawkeye running back, Ozzie Simmons. Simmons was a rarity in that era: a black player on a major college football team. Dubbed the “ebony eel” by some sportswriters of the era, Simmons had come north to play football when he wasn’t allowed to play football in his home state of Texas, due to his race.

America in the 1930s included Jim Crow laws in southern states, which segregated blacks from whites. In northern states, no such laws existed, but discrimination was still widespread.

Simmons’ talent couldn’t be denied, however, and he attracted the attention of a young Iowa sports broadcaster perched high above the field. That broadcaster, who would become President Ronald Reagan, became an Ozzie Simmons fan, noted Minnesota Public Radio (MPR), which aired the story “The Origin of Floyd of Rosedale” in 2005. Reagan described a trademark Simmons’ move during a telephone interview with legendary Iowa sports broadcaster Jim Zabel of WHO Radio in Des Moines.

“Ozzie would come up to a man, and instead of a stiff-arm or sidestep or something, Ozzie — holding the football in one hand — would stick the football out,” Reagan said. “And the defensive man just instinctively would grab at the ball. Ozzie would pull it away from him and go around him.”

There were no dazzling runs against Minnesota, however, in the 1934 game at Iowa. Simmons was knocked out three times, leaving the game for good by halftime. The Gophers overwhelmed Simmons and the rest of the Iowa team, beating them 48-12.

While Minnesota went on to win the national championship that year, Iowa fans at the game were outraged by how Minnesota played, in Iowa City claiming the defense deliberately went after Iowa Simmons hard. (Just 11 years earlier, Iowa State’s first black athlete, Jack Trice, died of injuries sustained in a game at Minnesota in 1923.)

How Floyd of Rosedale was born

In 1935, the Rosedale Trophy debuted in an attempt to generate some goodwill between the two schools. Ahead of the 1935 game, Herring warned Minnesota not to pull the same stunts it did the year before. “If the officials stand for any rough tactics like Minnesota used last year, I’m sure the crowd won’t,” Herring said.

Olson sent a telegram to Governor Herring to assure him that the Minnesota team would tackle clean. To help calm the growing tension ahead of the next Minnesota-Iowa football game, Olson also went on to say that he would bet a prize pig from Minnesota against a prize pig from Iowa that Minnesota would win the big game. The loser would have to deliver the pig in person.

“Dear Clyde,” stated Olson’s telegram to Herring. “Minnesota folks are excited over your statement about the Iowa crowd lynching the Minnesota football team. If you seriously think Iowa has any chance to win, I will bet you a Minnesota prize hog against an Iowa prize hog that Minnesota wins today.”

The Iowa governor accepted, and what became known as the Floyd of Rosedale prize was born. Herring apparently followed Olson’s cue. He joked it would be hard to find a prize hog in Minnesota, since they all were so “scrawny.”

Floyd of Rosedale trophy

Word of the bet reached Iowa City as the crowd gathered at the stadium. Things calmed down, and the game proceeded without incident. Minnesota won 13-7.

The prize pig from Iowa was a Hampshire boar, black with a white belt. He was later named the Floyd of Rosedale after Minnesota’s governor. In the week following the big game, Herring delivered the live pig to the Minnesota Capitol building in St. Paul and took Floyd inside to meet Olson.

After the hog’s trophy days were over, Floyd spent his remaining days on a farm in southeast Minnesota. Floyd died of hog cholera in July 1936, about eight months after he made the front page. The real Floyd, Governor Olson, passed away less than a month later, dying of cancer in August 1936.

(Ironically, Floyd the hog wasn’t the only celebrity in his family. Floyd of Rosedale was the brother of another famous boar, Blue Boy, who had appeared in the 1933 movie “State Fair.”)

Leaving a legacy

All these years later, the famous Floyd of Rosedale endures as one of college football’s most famous trophies. Floyd of Rosedale’s legacy is also preserved in a marker by the Rosedale Rapids Aquatic Center in Fort Dodge.

Simmons, whose story prompted the Floyd of Rosedale trophy, never took much interest in the trophy, in part because of the era of racial discrimination it recalled. He was denied a chance to play professional football, because the National Football League banned black players at the time, noted MPR. He played some minor league ball, joined the Navy and eventually became a Chicago public school teacher.

“When Ozzie Simmons stepped onto the field in October, 1934, to play Minnesota, he entered a national drama that’s still playing out today,” MPR noted. “All Simmons wanted was a chance. The trophy is an ever-present reminder of how precious that right is.”

Want more stories like this?

These are the kinds of stories I’m sharing in my new book, “Iowa Agriculture: A History of Farming, Family and Food,” which was released by The History Press on Monday, April 27, 2020. Order your signed copy by clicking here to my online store.

One more thing–the story of illegal gambling

After I posted this story, I received this intriguing email from my friend Victoria Herring of Des Moines:

“You may remember coming to Artisan Gallery 218 to do book talks. I was reading your website about the Floyd of Rosedale story – apparently appearing in an upcoming book. I assume you know there’s a bit more to the story == I think George Mills wrote about it in one of his books == when this happened some guy [whose name I forget but he was a bit of a thorn in the side of some public figures] filed a criminal complaint against Gov. Herring [he was my grandfather] alleging illegal betting — might be an interesting even if a little off topic addition.”

I pulled out a copy of George Mills’ classic book, Looking in Windows: Surprising Stories of Old Des Moines, and saw exactly what Victoria was talking about. In the second called “A Governor Arrested,” Mills explained how a gadfly named Virgil Case in Des Moines got a warrant for Governor Herring’s arrest following the Floyd of Rosedale 1935 bet. The charge? Gambling on a hog wager.

At the time, Iowa law provided a penalty of up to a $100 fine or 30 days in jail for gambling. Municipal Judge J.E. Mershon signed the warrant.

Who was Case and why did he go to all this trouble? He was a “natural-born hell raiser,” wrote Mils, who added that Case had been a secretary to a Des Moines mayor and publisher of a weekly newspaper.

Case explained how he happened to file the charge. He said he had some spare time, and it occurred to him a “good way to put in that time was to go over to Municipal Court and have the governor arrested. So that’s what I did.” He said his profession was “raising hell with public officials because they should be the first to set a good example.”

Word of the warrant reached Herring while he was still with Minnesota Governor Olson in Minneapolis. Herring immediately engaged Olson as his attorney. Olson squelched a suggestion that the pig be auctioned off to pay a possible Herring fine. “That pig stays in Minnesota, regardless of what happens,” Olson declared. He added that the bet wasn’t a gamble anyway, since Minnesota was a cinch to win the game.

Olson suggested that Herring stay in St. Paul, where he couldn’t be extradited, since the Minnesota governor had to consent to the extradition, and Olson was already Herring’s attorney. Herring observed that only the governor of Iowa could extradite anyone back to Iowa–and he was the governor of Iowa.

“Olson added a sly insult when he said it wasn’t gambling because ‘nothing of value was involved,'” Mills wrote. Herring shot back that Floyd of Rosedale was a “right good hog.”

Walter Brick, deputy municipal court bailiff, cause a stir of excitement at the Iowa statehouse a few days later. When he showed up at Herring’s office, reporters thought maybe he was there to lead the governor away in handcuffs. Nope. Brick just wanted to talk over a planned court hearing on the charge.

The only action the deputy took that day was to join the reporters in eating apples out of Herring’s fruit basket. (“Beside apples, Herring was known at times to shut the door and provide the press with beer and Pella bologna, something no governor has done since,” Mills wrote.)

In the hearing, reporters and others testified that Herring hadn’t committed the so-called offense in Des Moines, that the bet wasn’t complete until Herring and Olson met in Iowa City. Assistant Polk County Attorney C. Edwin Moore, later chief justice of the Iowa Supreme Court, moved that the case be dismissed. Judge Mershon was glad to do so. “The folderol was over,” Mills concluded.

Want more?

Thanks for stopping by. I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you value intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, agriculture updates, recipes and tips to make you a better

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press. Also take a look at my latest book, “Dallas County,” and my “Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing. Both are filled with vintage photos and compelling stories that showcase he history of small-town and rural Iowa. Order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page, or click here. Feel free to share this with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

Also, if you or someone you know could use my writing services (I’m not only Iowa’s storyteller, but a professionally-trained journalist with 20 years of experience), let’s talk. I work with businesses and organizations within Iowa and across the country to unleash the power of great storytelling to define their brand and connect with their audience through clear, compelling blog posts, articles, news releases, feature stories, newsletter articles, social media, video scripts, and photography. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com, or e-mail me at yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com, and yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Talk to you soon!

Darcy

Memories of Carroll County, Iowa, Century Farm Endure

Among the most remarkable parts of rural Iowa are the thousands of families who have owned the same land for 100 years. I’ve had the chance to interview hundreds of Iowa families who own Century Farms. Some of these folks, like Bill Bruggeman, share the kinds of stories you never forget.

After Bill passed away this week (read his touching obituary here), I felt that sharing his story would be a fitting tribute to a dedicated, kind, hard-working Iowa farmer I respect greatly Here’s his story, which I wrote in 2017 for Farm News:

While all the buildings that once graced the Bruggeman family’s Carroll County Century Farm between Lidderdale and Lake City are gone, the memories live on.

“The times keep changing,” said Bill Bruggeman, 85, who lives with his wife, Doris, on a farm a few miles northeast of his family’s Sheridan Township Century Farm. “This spring I saw a farmer on RFD TV who could plant 2,500 acres a day. This country is going big.”

It’s a big switch from the 120-acre Carroll County farm that Bruggeman’s grandfather, John Bruggeman, purchased in 1903. John and his wife, Emma, had farmed near Johnson, Nebraska, before deciding their farming prospects were brighter back in Iowa.

While Bruggeman didn’t grow up on the Century Farm where his grandparents lived, he has fond memories of the farmstead, which once boasted a large farmhouse and barn. “When I was a little kid I’d go across the fields on Saturday mornings to get Grandma Emma’s fresh-baked cinnamon rolls,” he recalled.

Good food was perk of farm life, which was often filled with long days of hard work and few luxuries. “We didn’t get electricity on the farm until the 1940s and didn’t get running water until the 1950s,” Bruggeman said.

Horsepower sometimes came from the family’s Farmall tractor, but it also came in the form of May and Babe. “I loved that team,” said Bruggeman, whose family used the horses to plant corn, pull the manure spreader and haul hay. “They didn’t run away.”

Those were the days when 12 neighborhood families worked together in a threshing ring, a tradition that lasted until the mid-1950s. While Bruggeman’s father, Carl, and the other men worked in the field, Bruggeman’s mother, Marie, prepared fried chicken, roast beef, mashed potatoes, fruit pies, cream pies and more to serve the hungry men at noon.

“Around 5 p.m. you’d haul the last load of the day,” said Bruggeman, who noted that the wives provided the threshing crew with snacks around 3 p.m. “The men were usually served supper, too.”

The day’s work wasn’t done, however, since each farmer had chores to do at home. “Back then, many farms had about 20 beef cows, some dairy cows and about 10 sows,” Bruggeman said.

While the demands of farm work limited trips to town, there was fun to be had when it to was time to buy groceries. Bruggeman enjoyed the outdoor movies shown in Lidderdale in the summer months, back when the town had three grocery stories and about as many gas stations. “Dad would give me a nickel so I could get a pop or popcorn,” said Bruggeman, who recalled how cars were lined up on both sides of the town’s busy business district.

Money was hard to come by in those days, and crop yields were nowhere close to what farmers produce today. “When I was a kid, 60 bushels per acre of corn was a really good yield,” said Bill Bruggeman, who started farming full-time in 1955 after completing his military service. As improved corn hybrids become available, Bruggeman won the DEKALB Yieldmasters Club award in 1976 for producing 113.39 bushels of corn per acre.

While much has changed in agriculture since the Bruggemans were raising their four children (including Sheila, Brenda, Cathy and Brett) on the farm, the family is proud to honor the legacy of their Century Farm, which is now owned by Brett Bruggeman.

“It’s wonderful to have a Century Farm,” said Bruggeman, who retired from farming three years ago. “We’re lucky to have one.”

Bruggeman Carroll County Century Farm

• Established: 1903

• Township: Sheridan

• Acres: 120

• Century Farm Award given in 2016

• 4th generation farm

Want more?

Thanks for stopping by. I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you value intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, agriculture updates, recipes and tips to make you a better

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press. Also take a look at my latest book, “Dallas County,” and my “Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing. Both are filled with vintage photos and compelling stories that showcase he history of small-town and rural Iowa. Order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page, or click here. Feel free to share this with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

Also, if you or someone you know could use my writing services (I’m not only Iowa’s storyteller, but a professionally-trained journalist with 20 years of experience), let’s talk. I work with businesses and organizations within Iowa and across the country to unleash the power of great storytelling to define their brand and connect with their audience through clear, compelling blog posts, articles, news releases, feature stories, newsletter articles, social media, video scripts, and photography. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com, or e-mail me at yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com, and yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Talk to you soon!

Darcy

Senator Grassley on Farming: Any Society is Only Nine Meals Away From a Revolution

When people ask about my latest book project and I tell them about Iowa’s Ag History, I get two reactions: either a blank stare, or “Oh cool!” When I reached out to Iowa Senator Charles Grassley, a farmer, to share a few comments for the book, I received more than an enthusiastic response.

I got an incredible interview from a senator who was willing to offer a significant portion of his time to share his insights into the importance of history, agriculture and rural Iowa’s role in the modern global economy. Read on to see why Sen. Grassley says, “I like to remind policymakers that any society is only nine meals away from a revolution.”

When did your family start farming in Iowa?

I am the second generation farmer in my family, following in the footsteps of my father Louis Grassley. His dad emigrated from Germany and died when my dad was just seven years old. At around age 18, my dad started working as a hired hand for the Heitland family on a farm in Hardin County. A few years later, he rented some land near New Hartford in Butler County. In 1927, he and my mother Ruth purchased their own parcel of land.

After graduating from high school, I worked in factories, attended college and farmed with my dad. In 1958, while running for the Iowa legislature and working towards my doctorate at the University of Iowa, I started farming my own piece of the family farm. When my dad passed away in 1960, I rented his 80 acres and about five years later, purchased 120 acres on my own.

When I started out, I grew a bit of everything like most farmers at the time. I grew corn, soybeans, oats and alfalfa and raised sheep, cattle and hogs. My son Robin Grassley, a third-generation farmer, and I continue farming 750 acres together. He rents and owns other farmland along with my grandson Pat Grassley, who is a fourth-generation family farmer.

Barbara and I raised our five children together on our farm near New Hartford, and we enjoy passing on our agrarian heritage and celebrate family gatherings here with our grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

In politics as in farming, a solid understanding of the past is vital to understand current issues. From your unique viewpoint as a senator and a farmer, what’s your take about why it’s important to be well-versed in history–and what are the perils of not knowing history?

As a lifelong farmer who also has worked for six decades representing Iowans in state and federal government, I wear my rural roots as a badge of honor and believe it’s important for farmers to have a seat at the policy-making tables. Farmers take the long view of things, and maybe that’s why they don’t forget important lessons from history.

Only two percent of the American population shoulders the responsibility for growing enough food to feed the U.S. population. Our agrarian-based heritage has experienced rapid transformation in the last generation. Fewer Americans, even in Iowa, have a direct link to living or working on a farm. And most likely due to the affordable abundance of food, not enough people appreciate that food security is directly tied to national security. Food security extends beyond national sovereignty. American agriculture – and the farmers, workers and businesses along the supply chain – anchors the U.S. economy and increasingly strengthens U.S. energy independence, as well.

From a historical perspective, there are two rules of thumb I use to explain how important food security is to maintain peace and prosperity in society. As Emperor of France in the early 19th century, Napoleon Bonaparte reportedly said “to be effective, an army relies on good and plentiful food.” In other words, an army marches on its stomach. Food security ensures a nation can feed its military, whose men and women in uniform are deployed to protect and defend a nation’s sovereignty, at home and abroad. I also like to remind policymakers that any society is only nine meals away from a revolution.

Political leaders who embrace the misguided notion that socialism is the answer to peace and prosperity are either grossly misinformed or willfully ignorant about the peril of leaders who promise to fix “inequality” with government control. Just look at the economic crisis in Venezuela, once one of the most prosperous nations in the Western Hemisphere. The poverty and humanitarian crisis falls squarely in the hands of the nation’s authoritarian regime and its ideologically driven policies. History teaches us that when government suppresses freedom and liberty, the people’s path towards peace and prosperity is replaced with food and medicine shortages, hyperinflation, power outages and even more economic and social inequality.

History teaches us other important lessons. Namely, how not to repeat the mistakes of the past. Don’t forget, the overly harsh tariffs in the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1932 shut down world trade, led to a worldwide economic depression and foretold a world war that killed tens of millions of people.

Another important lesson I keep in mind at the policy-making tables is the 1980s farm crisis. The loss of thousands of family farms was a heart-wrenching loss for so many families and long-time neighbors across Iowa. It stole a sense of vitality from small towns and rural communities. It arguably steered away a generation of beginning farmers from following in the footsteps of their parents and grandparents. The farm crisis invigorated my advocacy on behalf of young and beginning farmers, including my work to push for robust enforcement of anti-trust laws and oversight of mergers and competition in the agriculture industry. Previously, I’ve introduced legislation that would have amended the Packers and Stockyards Act to make it illegal for a packer to own, feed or control livestock intended for slaughter. I’ll keep my oversight hat on to protect the integrity of the marketplace so that independent producers have a fair shake at a fair price for their commodities.

I also led efforts to enact and make permanent Chapter 12 in the federal bankruptcy code. This unique chapter is designed to help farmers and ranchers who have fallen on hard times to survive bankruptcy and restructure their debts without losing their livelihood. Most recently, I secured an update to Chapter 12 to fix court rulings that undermined congressional intent. Previously, the IRS muscled its way to the front of the creditor’s line to scoop up capital gains taxes and potentially block a farmer’s reorganization plans. Farmers shouldn’t be penalized for being asset-rich and cash-poor. When they need to reorganize debts to hold on to their livelihoods, my reforms ensure they aren’t going to be slapped with a big tax bill and lose the ability to continue farming.

Another way I advocate for family farmers at the policy-making tables is my longstanding efforts to restore fiscal integrity to the farm safety net. In our free market society, farmers ought to be able to decide how large or small they want their operation to be. However, the farm safety net shouldn’t be manipulated for operations to grow at taxpayer expense. It’s very important to uphold the credibility and strengthen the public trust in the farm safety net, as well. That’s why I will continue my efforts to attach reasonable payment limits so that off-site managers, including nieces, nephews, cousins and other family members who aren’t actually contributing to the operation of the farm, are prevented from cashing in on farm payments.

In 2019, I launched my 39th consecutive year holding meetings in each of Iowa’s 99 counties. I keep in close touch with Iowans and count on this dialogue to make representative government work. I also apply the lessons of history to inform my work on making better policies and fixing laws that create unintended consequences. As chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, which has oversight and legislative jurisdiction over international trade, I’m currently working to reform a 1962 federal law that delegated authority to the executive branch. Specifically, Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act authorizes the president to impose tariffs on selected imports if the chief executive determines those imports pose a threat to our national security.