Category: Iowa history

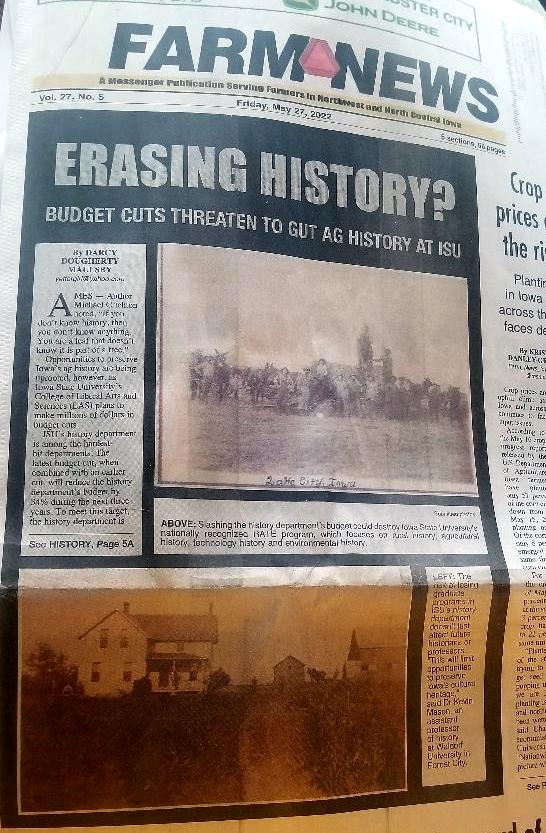

Erasing History? Budget Cuts Threaten to Gut Ag History at Iowa State University

Author Michael Crichton noted, “If you don’t know history, then you don’t know anything. You are a leaf that doesn’t know it is part of a tree.” Opportunities to preserve Iowa’s ag history are being uprooted, however, as Iowa State University’s (ISU) College of Liberal Arts and Sciences (LAS) plans to make millions of dollars in budget cuts.

ISU’s history department is among the hardest-hit departments. The latest budget cut, when combined with an earlier cut, will reduce the history department’s budget by 34% during the next three years. To meet this target, the history department is considering eliminating its graduate programs and search for further economies.

“The decisions made today influence the future,” said Michael M. Belding III, 31, a Ph.D. candidate studying rural, agricultural, technological, and environmental history at ISU. “I disagree with the budget cuts for ISU’s history department, because the people of Iowa deserve better.”

Belding has been gathering signatures to challenge these budget cuts, which would eliminate graduate programs in ISU’s history department.

Michael M. Belding III, a Ph.D. candidate studying rural, agricultural, technological, and environmental history at Iowa State University (ISU), has been gathering signatures to challenge severe budget cuts that would eliminate graduate programs in ISU’s history department.

He took action after Dr. Beate Schmittmann, LAS dean, announced a new round of budget cuts as part of her “Reimagining LAS” initiative. This is intended to “right-size” the budget in response to changing enrollment and student demand and “to position the college for future success,” according to ISU.

Slashing the history department’s budget will destroy ISU’s nationally-recognized RATE program, which focuses on rural history, agricultural history, technology history and environmental history. “If these proposed budget cuts occur, ISU is throwing away an innovative, important program,” noted Dr. Pamela Riney-Kehrberg, a distinguished professor of history at ISU.

If this happens, there will be long-lasting, negative impacts for Iowa, added Dr. Joe Anderson, a professor of history at Mount Royal University in Calgary, Alberta. “The Midwest has long been dynamic powerhouse of agriculture and innovation,” said Anderson, who earned his Ph.D. in history at ISU. “Everyone who cares about Iowa and its past should be mad as hell about ISU’s decision.”

Iowa’s ag heritage isn’t just for history majors

The risk of losing graduate programs in ISU’s history department doesn’t just affect future historians or professors. “This will limit opportunities to preserve Iowa’s cultural heritage,” said Dr. Kevin Mason, an assistant professor of history at Waldorf University in Forest City.

Not everyone who enrolls in history classes at ISU is a history major, added Mason, who received his Ph.D. in rural and environmental history from ISU in 2020. They include attorneys, engineers, architects and high school teachers who want to expand their knowledge of Iowa’s heritage. “If you care about Iowa history, you need to understand ag history.”

The only other university offering anything similar to ISU’s RATE program is Mississippi State University (MSU), although MSU focuses on Southern—not Midwestern—history. Neither the University of Iowa nor the University of Northern Iowa focus on ag/rural history, Riney-Kehrberg added.

“In most history courses and books, there’s little or no information on ag history following the Civil War,” noted Riney-Kehrberg, who researches American rural and agricultural history and will soon publish her latest book, When a Dream Dies: Agriculture, Iowa and the Farm Crisis of the 1980s. “The standard American history textbook might have one sentence about the Farm Crisis.”

The same dearth of information is evident when it comes to the role of women in agriculture. “There are many women’s studies courses today, but they often only teach the story of urban women, not rural women,” Riney-Kehrberg added.

“If these proposed budget cuts occur, ISU is throwing away an innovative, important program,” notes Dr. Pamela Riney-Kehrberg, a distinguished professor of history at Iowa State University.

History comes to life through the “land-grant land hunt”

While Yale University offers agrarian studies, it’s not the boots-on-the-ground style of research and extension that a land-grant university like ISU provides, Riney-Kehrberg noted.

Brandon Duxbury experienced this first-hand through the “land-grant land hunt” that ISU Extension undertook from 2014-2018. Contrary to popular belief, not a single acre of Story County land was given to Iowa State as part of the land-grant act (the Morrill Act) of 1862. Iowa was the first state to accept the provisions of the Morrill Act to build a college for the study of agriculture and the mechanical arts. Iowa Governor Samuel Kirkwood appointed Peter Melendy to select the best 210,000 acres of Iowa land to fund the new land-grant college. Most of this land was available in north-central and northwest Iowa.

Iowa became the first state to digitally map all these land-grant parcels within the state. Duxbury, a South Dakota native and graduate student in ISU’s history program, researched countless historical documents and interviewed current landowners to share their stories of their farmland. “People were always excited when we contacted them about this project,” said Duxbury, who is the new curator of collections at the Dacotah Prairie Museum in Aberdeen, South Dakota.

These stories, videos, a digital map and more can be found at www.landgrant.iastate.edu. “Efforts like this inspire people to ask better questions about the legacy they’re leaving with the land,” Duxbury said.

Making Iowa history relevant in ways like this is vital, said Belding, a Story City native who has links to his petitions on his Twitter account @mickey_belding. “I grew up thinking history involved big events that happened elsewhere, not here in Iowa. The more I research Iowa’s ag history, though, the more attached I get to Iowa.”

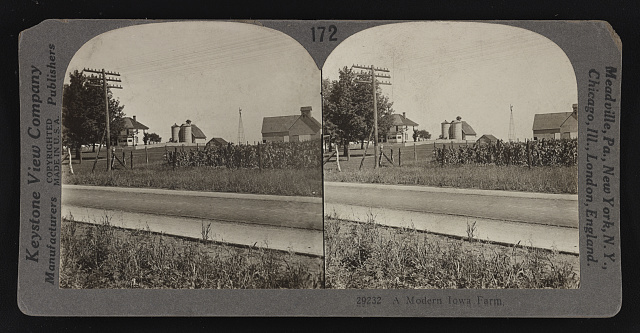

Family farms like this one near Yetter in Calhoun County have driven the economy in Iowa and the Midwest for generations. “The Midwest has long been dynamic powerhouse of agriculture and innovation,” says Dr. Joe Anderson, a professor of history at Mount Royal University in Calgary, Alberta, who earned his Ph.D. in history at Iowa State University (ISU). “Everyone who cares about Iowa and its past should be mad as hell about ISU’s decision.”

Teaching history prepares students for success

Along with researching and preserving Iowa history, ISU’s history department helps students develop a broad skill set, including communication. “My dad was a computer programmer who was promoted to management,” Riney-Kehrberg said. “He always emphasized that reading, writing and speaking skills were essential for a successful career.”

History classes also teach students research skills, data analysis and critical thinking. “You have to make an argument, and then find facts to support this argument,” Riney-Kehrberg said. “All this requires you to think carefully and broadly.”

Studies show that students with a solid LAS education, including history, have some of the best outcomes five years after college graduation. “These graduates tend to make more money, are the least likely to be fired, are less likely to move back home to live with their parents and are more likely to be promoted,” said Anderson, citing sources like the 2018 report “Humans Wanted: The Coming Skills Revolution,” published by the Royal Bank of Canada. “We’re very short-sighted as a culture if we devalue skills that come from studying the humanities.”

The “soft skills” of how people communicate with each other, interact with colleagues and solve problems are just as important to workplace readiness and employability as hard skills, especially as technology evolves. “It doesn’t take a ‘George Jetson’ moment to imagine a day when artificial intelligence and other technologies will replace some of the jobs we currently train people for,” Anderson, who served as director of history and interpretation at Living History Farms in Urbandale in the 1990s. “Our society will always need people who are skilled in human connection and communication.”

Society also needs educated citizens, both rural and urban, with a solid understanding of agricultural history, Anderson added. “People who are trained in ISU’s history department often go on to run museums in Iowa and the Midwest, teach at community colleges like DMACC or Hawkeye Community College, teach at land-grant universities, or pursue a variety of other careers.”

Everywhere they go, these professionals take Iowa history with them, noted Anderson, a south-central Nebraska native who loved spending time on his grandparents’ farms in Missouri and Iowa. He often incorporates Midwestern history into the classes he teaches in Canada. “This perspective helps people better understand many pressing issues today, from water quality to food production.”

Integrating history with tourism, economic development

It’s essential to be open to new ways of making Iowa history relevant to a wider audience, Mason said. “I believe history departments, especially at a land-grant like ISU, can collaborate across academic disciplines to help create a more diversified economy that encourages young people to stay in Iowa.”

Mason, who grew up in Pella, saw how Iowa history was intertwined with job creation, economic development and tourism in his hometown. “Tradition is important in Pella. Honoring this heritage helps young people gain a sense of place and the sense of pride that comes from knowing their history.”

Anyone who is concerned about the proposed funding cuts to ISU’s history department should contact their state legislators, the Board of Regents, and Dr. Beate Schmittmann, dean of the College of LAS at ISU. It’s important to take action now, Duxbury said. “The loss of ISU’s graduate history programs is a loss to Iowa history. Fighting these drastic cuts is a battle worth fighting.”

Note: I wrote this article for Farm News. It first appeared in the Friday, May 27, 2022, edition of Farm News. I’ve had a number of people ask me what they can do to fight these budget cuts. First, if you’re an Iowan, contact the senator and representative who represent you at the state level in the Iowa legislature. Also, contact leaders at ISU, including:

Iowa State University

Attn. Dr. Beate Schmittmann

202 Catt

2224 Osborn Dr.

Ames IA 50011-4009

Iowa State University

Office of the President, Dr. Wendy Wintersteen

515 Morrill Road

1750 Beardshear Hall

Ames, IA 50011

Want more?

I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you value intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, agriculture updates, recipes and tips to make you a better communicator.

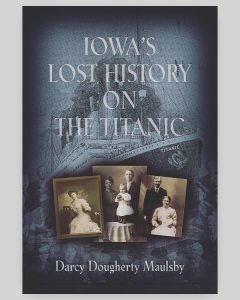

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press. Also take a look at my other books, including “Iowa Agriculture: A History of Farming, Family and Food” from The History Press, “Madison County,” “Dallas County” and “Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing. All are filled with vintage photos and compelling stories that showcase the history of small-town and rural Iowa. Click here to order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page, or click here. Feel free to share this with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

Also, if you or someone you know could use my writing services (I’m not only Iowa’s storyteller, but a professionally-trained journalist with 20 years of experience), let’s talk. I work with businesses and organizations within Iowa and across the country to unleash the power of great storytelling to define their brand and connect with their audience through clear, compelling blog posts, articles, news releases, feature stories, newsletter articles, social media, video scripts, and photography. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com, or e-mail me at yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com, and yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Talk to you soon!

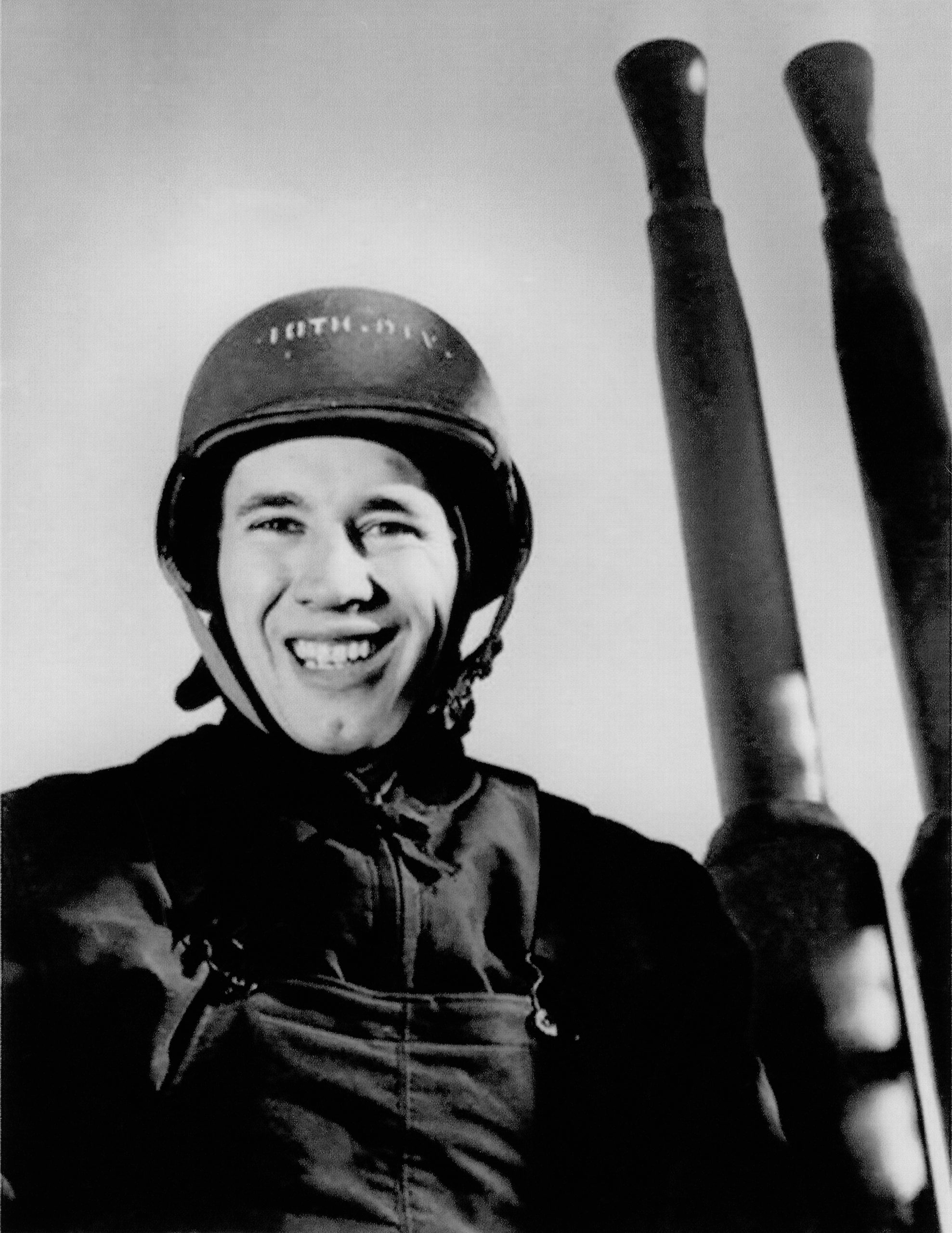

Bob Feller on Farming, Baseball and Military Service

Now that we’re in the time of the year when we take time to honor those who’ve served (Memorial Day), celebrate America (July 4) and maybe even catch a baseball game, I think about the time I interviewed Bob Feller, a Major League Baseball legend and Iowa farm kid.

I’m willing to bet that most people, if they are old enough to remember Feller, know him more for his pitching prowess with the Cleveland Indians. But Feller was also a decorated World War II veteran who gave up some of his prime years of playing professional baseball to serve his country.

“I’m very proud of our military and have a lot of respect for our troops,” said Feller (1918-2010) when I interviewed him in his hometown of Van Meter, Iowa, in 2003.

Known as the “Heater from Van Meter,” Feller signed a pro baseball contract with the Cleveland Indians when he was only 16. “Farm work made me a ball player,” Feller said. “When I was little, I was the water boy for the threshing crew. As I got older, I did it all—I cleaned the barn, milked cows, drove tractors and teams of horses, picked corn and threw bales of hay. Those bales really helped strengthen my arms.”

Feller’s father, Bill, was his first coach. “When I was a kid, Dad built a ball field we called Oak View. That was the first Field of Dreams—not that one from the movies.”

Feller grew up playing baseball at vacation Bible school at the Methodist Church in Van Meter. He also played four years of American Legion baseball in Adel, where his catcher was Nile Kinnick, a future University of Iowa football star who would enlist in the Navy Air Corps Reserve three days after the attacks on Pearl Harbor.

Feller’s father spent hours helping his son develop his baseball skills. “Dad would hit ground balls to me in the hog lot and pitch batting practice to me. We’d practice every night we could. When Mom would call us for supper, we’d always tell her we could eat after dark, but we couldn’t play ball after dark.”

“I never thought twice about enlisting”

By the time Feller played his first game in the major leagues in 1936, the teenaged pitcher struck out 15 St. Louis Browns. Later that season, at age 17, Feller set a new American League record by fanning (striking out) 17 Philadelphia Athletics. In Chicago in 1940, Feller pitched his first of three no-hitters and the only no-hitter pitched on opening day in major league history. On the eve of World War II, Feller was playing in the big leagues with stars like Ted Williams and Joe DiMaggio. By the time Feller enlisted in the Navy two days after the Pearl Harbor attacks on December 7, 1941, the 22-year-old star had already set a number of major league records.

On the eve of World War II, Feller was playing in the big leagues with stars like Ted Williams and Joe DiMaggio. By the time Feller enlisted in the Navy two days after the Pearl Harbor attacks on December 7, 1941, the 22-year-old star had already set a number of major league records.

While some say Feller’s military service took away what could have been some of his most productive years, Feller doesn’t see it that way.

“I never thought twice about enlisting. I played a little baseball during boot camp in Norfolk, Virginia, before I became an anti-aircraft gun captain on the USS Alabama for 34 months.”

Feller was awarded eight Battle Stars during his years of service. When the war ended, Feller resumed his baseball career with the Cleveland Indians in the late summer of 1945. “I’m no hero,” emphasized Feller, who was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1962, after retiring from baseball in 1956 at age 37. “I’m just a survivor. The men who never returned home to this country were the heroes.”

Maybe Feller’s story resonates me so much because I, too, come from rural Iowa, and I’ve been blessed to know many friends and family members who have served our country. America is home to a significant percentage of veterans. In 2011–2015, nearly one fourth (24.1 percent) of the veteran population 18 years and older lived in areas designated as rural, according to census.gov.

While we don’t know them all, we owe them all. Thanks to you all, and thanks to patriots like Bob Feller who was willing to serve when his country needed him. America truly is the home of the free because of the brave.

Want more?

I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you value intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, agriculture updates, recipes and tips to make you a better communicator.

I’ve shared more Bob Feller stories and photos in my Iowa history book “Dallas County.”

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press. Also take a look at my other books, including “Iowa Agriculture: A History of Farming, Family and Food” from The History Press, “Madison County,” “Dallas County” and “Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing. All are filled with vintage photos and compelling stories that showcase the history of small-town and rural Iowa. Click here to order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page, or click here. Feel free to share this with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

Also, if you or someone you know could use my writing services (I’m not only Iowa’s storyteller, but a professionally-trained journalist with 20 years of experience), let’s talk. I work with businesses and organizations within Iowa and across the country to unleash the power of great storytelling to define their brand and connect with their audience through clear, compelling blog posts, articles, news releases, feature stories, newsletter articles, social media, video scripts, and photography. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com, or e-mail me at yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com, and yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Talk to you soon!

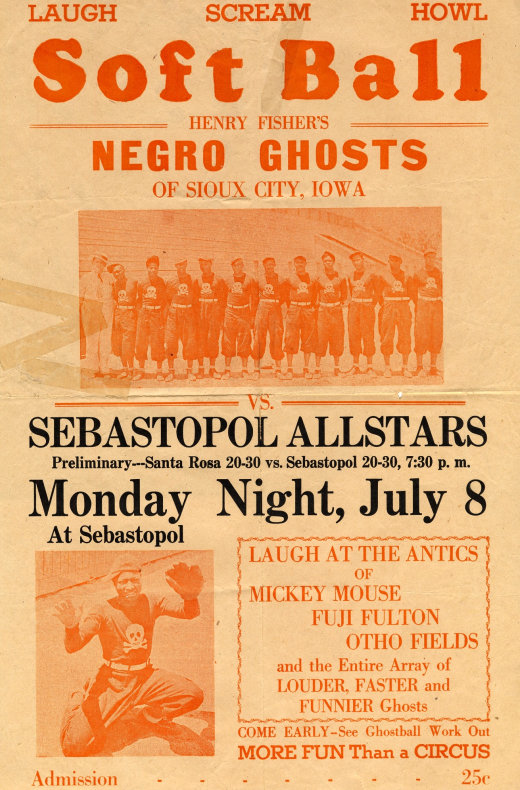

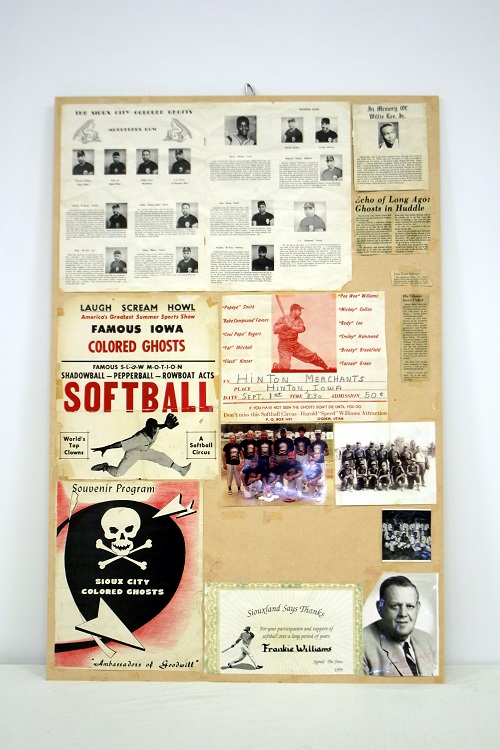

Remembering the African-American Sioux City Ghosts Fast-Pitch Softball Team

Even though owners and players of Major League Baseball are at an impasse trying to negotiate a 2020 season, there are still some noteworthy “boys of summer” stories to share, thanks to Iowa history. Perhaps no team brought more excitement to Iowa farm towns and cities across the country than the Sioux City Ghosts, a legendary African American fast-pitch softball team that got its start nearly 100 years ago.

“The Sioux City Ghosts were a big deal across the nation and internationally,” said Haley Aguirre, archival records clerk with the Sioux City Public Museum, which preserves some of the Ghosts’ history.

Because of their pranks on the softball field, the Sioux City Ghosts were often compared to the famous Harlem Globetrotters. The Sioux City team’s exceptional athletic skills, winning record and razzle-dazzle style of playing generated a level of excitement few teams have matched.

The team stemmed from a boys’ club the West 7th Street neighborhood of Sioux City, which was home to many African-American homes and businesses. This boys’ club team started with about 40 members in 1925. Many of the boys were brothers, and most players thought of their team as a family. Soon after forming, they became Sioux City’s Junior League champions, according to siouxcityhistory.org.

As the team members grew up, they entered Sioux City’s Senior League and again won the championship game. As they became well known in Sioux City, they received sponsorship from local businessman Jack Page. They wore uniform shirts with the team name – Jack-The Cleaners, but had no uniform pants. Instead, they wore whatever they owned, from jeans to bib overalls.

With the sponsorship of Jack’s, the softball team began playing in the tri-state area, but mostly in Iowa. As they toured, the nation was falling deeper into the Great Depression. Baseball and softball helped people forget about the poor economy, if only for a little while.

The Sioux City team grew in popularity the more the players toured. By 1933, they were known as the Sioux City Ghosts. Henry “Fats” Fisher became their first manager. That same year they also had a new sponsor, Whitney Cleaners, along with new uniforms. The black shirts and pants featured an orange skull and crossbones logo, which became the symbols of the Ghosts.

In 1934, Fisher convinced the Ghosts to tour in California, but only after their Iowa tour was complete. The players were an immediate hit in California, thanks to a few improvised comedy routines on the field.

Pitching style and substance

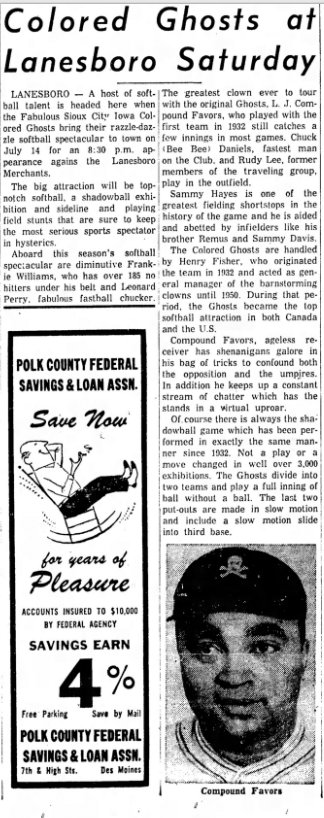

Starting in the early 1930s, the team began concentrating on the comedy routines and pranks for their games. One of the Ghosts’ favorite routines was shadowball. A Carroll Daily Times Herald article from July 12, 1962, described the spectacle.

“Of course, there is always the shadowball game, which has been performed in exactly the same manner since 1932. Not a play or a move changed in well over 3,000 exhibitions. The Ghosts divide into two teams and play a full inning of ball without a ball. The last two put-outs are made in slow motion and include a slow-motion slide into third base.”

The Ghosts were true showmen, sometimes pitching melons instead of softballs. They also rode bicycles in the outfield. Showcasing these stunts didn’t mean the Ghosts’ record suffered, though. They team often played the best amateur teams cities had, including farm leagues, all-star teams and state champions. The Ghosts won more than 2,000 games and lost less than 100 games during a 20-year span, noted siouxcityhistory.org. The Ghosts even challenged the Harlem Globetrotters’ softball team to a game, although the game was never played.

The Ghosts toured Canada and the western United States, playing in Las Vegas, Phoenix and San Francisco. Some of the Ghosts’ games attracted huge audiences. In Vancouver, Canada, 26,000 people came to watch the game.

While the Sioux City Ghosts were celebrated on the field, things were much different when the game was over. Many of the better players tried to move into the professional leagues, but couldn’t because they were black.

“The Ghosts actually didn’t play in a league,” Aguirre added. “They toured and basically played anyone who would get on the field with them. They faced substantial racism and prejudice, and were often at the mercy of those living in the towns they visited.”

The team broke up at the beginning of World War II when many of the players entered the armed forces. The Ghosts resumed playing as a team, however, after the war. While players from other teams were added from time to time, the Ghosts always remained a mostly Sioux City team.

Leaving a legacy

Leaving a legacy

The Ghosts included a variety of beloved players through the years, including Richard “Sitting Bull” Fields, “Oatie” Fields, Riley Fields, Willie Lee, Glenn Smith, Lawrence Freeman, Floyd “Fuji” Fulton, Benny Hamilton, Jamie Hicks, Clarence “Darby” Hicks, Rudy Lee, Major Ray, Fred Tolson, Robert Green, Vivian Johnson, Clayton Johnson, Bob Metcalf, Sam Davis, J.C. “Cool Papa” Johnson, Valse “Mickey Mouse” Metcalf, George “Smokey Joe” Murphy, Harold “Speedy” Williams, Reginald “Cricket” Williams, Frank “Papa Be Kind” Williams, Sam Hays, Benny Hamilton, Les “Spook” Wilkinson and L.J. “Bambino” Favors.

“Favors was quite the ball player,” Aguirre said. “He joined the Ghosts in 1934 and also played for the Colored House of David, Sioux City’s colored baseball team. He was inducted into the Iowa Men’s State Softball Hall of Fame in 1975.”

Favors was mentioned in the article “Colored Ghosts at Lanesboro Saturday,” which ran in the July 12, 1962, issue of the Carroll Daily Times Herald.

“The greatest clown ever to tour with the original Ghosts is L.J. Compound Favors, who played with the first team in 1932 and still catches a few innings in most games,” noted the article, which promoted the “razzle-dazzle softball spectacular” slated for July 14 at 8:30 p.m. against the Lanesboro Merchants. “Favors, an ageless receiver, has shenanigans galore in his bag of tricks to confound both the opposition and the umpires. In addition, he keeps up a constant stream of chatter, which has the stands in a virtual uproar.”

While Favors and his teammates thrilled audiences into the early 1960s in small Iowa towns like Lanesboro, Lake Park, Hinton and other communities, times were changing. One big milestone came in 1947, when Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier by becoming the first black athlete to play Major League Baseball (MLB) after joining the Brooklyn Dodgers.

With the integration of MLB, all-black teams like the Sioux City Ghosts became less common. While the last Sioux City Ghosts player, Franklin Williams, died in 2007, the team’s legacy lives on, thanks to the Sioux City Museum and the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., which preserves some of the Sioux City Ghosts’ memorabilia.

“The Ghosts helped put Sioux City on the map and acted as ambassadors of Iowa across the nation and internationally,” Aguirre said.

Want more?

I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you value intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, agriculture updates, recipes and tips to make you a better communicator.

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press. Also take a look at my other books, including “Iowa Agriculture: A History of Farming, Family and Food” from The History Press, “Dallas County” and “Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing. All are filled with vintage photos and compelling stories that showcase the history of small-town and rural Iowa. Click here to order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page, or click here. Feel free to share this with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

Also, if you or someone you know could use my writing services (I’m not only Iowa’s storyteller, but a professionally-trained journalist with 20 years of experience), let’s talk. I work with businesses and organizations within Iowa and across the country to unleash the power of great storytelling to define their brand and connect with their audience through clear, compelling blog posts, articles, news releases, feature stories, newsletter articles, social media, video scripts, and photography. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com, or e-mail me at yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com, and yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Talk to you soon!

Shattering Silence: Farmer Helped Slave Find Freedom and Racial Equality in Iowa

How much is your freedom worth? In 1834, it was worth $550 for a slave named Ralph Montgomery, whose tumultuous story would involve hope for freedom, dashed dreams, bounty hunters, tremendous risk and a groundbreaking court decision that continues to inspire Iowans to shatter the silence on the volatile issue of racial inequality.

“He was born into slavery, a piece of property allowed only to serve others,” noted the article “Iowa Supreme Court’s First Case Freed a Slave,” which ran in 2015 in The Courier newspaper in Waterloo. “Even his name belonged to someone else.”

He came into the world as Rafe Nelson, probably in about 1795. But early on Nelson became Ralph Montgomery, named for his slave master in Virginia. After being taken to Kentucky by his owner and namesake, Ralph was described as “quite a chunk of a field hand” in his 20s. Despite that fact — or perhaps because of it—Ralph Montgomery, the slave master, sold his slave to a brother.

The new owner, William Montgomery, then sold Ralph in 1830 to a son, Jordan Montgomery. Newspaper accounts of the era described Jordan Montgomery as “kind and indulgent.”

Jordan Montgomery subsequently took Ralph to Palmyra, Mo., located northwest of Hannibal, the famed Mississippi River town. Ralph served his owner for about two years in Palmyra, which was roughly 60 miles south of the Iowa border.

“Here [at Palmyra], Ralph met a white man named Ellis Schofield, who had just returned from a trip to the Upper Mississippi region’s lead mining regions. He told such glowing tales of boundless wealth to be acquired there that Ralph became “seized with a burning desire to go and work out his own salvation,” according to the Janesville Gazette in Wisconsin.

Seeking freedom in Iowa

Jordan Montgomery and Ralph worked out a written agreement sometime around 1834 or 1835, where Ralph committed to pay $550, with interest, for his freedom. He traveled northward, “strong of purpose and light of heart,” according to a story in the Janesville Gazette in 1870.

Ralph went to work mining lead in Dubuque in the Iowa Territory. After five years, however, he hadn’t been able to repay the debt. The problem was the high cost of living. Ralph apparently struggled simply to pay room and board, according to historian Dorothy Schwieder, author of the book Iowa: The Middle Land.

At the same time, Jordan Montgomery experienced financial difficulties, struggling to repay a $4,000 bank loan. When two men from Virginia offered to return Ralph to his cash-strapped master in Missouri for a fee of $100. Jordan Montgomery wasn’t inclined to write off Ralph as bad debt, so he accepted the bounty hunters’ offer.

Shattered dreams

The Virginians swore an affidavit in front of a justice of the peace that Ralph was a fugitive. Court official ordered the local sheriff to assist the bounty hunters. The group found Ralph at his mineral claim, put him in handcuffs and loaded him onto a wagon.

Alexander Butterworth, variously described as a farmer, businessman, concerned eyewitness and noble-hearted Irishman in the Dubuque area, was plowing a nearby field and saw the kidnapping. Butterworth dashed to Dubuque to notify Thomas Wilson, an associate judge on the newly formed Supreme Court of the Territory of Iowa.

Let’s take it to court

Judge Wilson ordered the sheriff to follow the bounty hunters who had seized Ralph and return bring Ralph to Dubuque. Armed with a writ of habeas corpus and accompanied by the sheriff, Butterworth galloped to the rescue, noted historical accounts.

The Virginians had managed to get Ralph to Bellevue, Iowa, along the Mississippi River to board a riverboat that would transport him back to Missouri. Butterworth and the sheriff reached the dock just in time. They ordered the riverboat captain to return Ralph to Dubuque for a hearing before Judge Wilson.

Ralph’s case would turn out to be the first decided by the Territory of Iowa’s Supreme Court, which had been established in 1838 in Burlington. The court’s inaugural case was titled “In the matter if Ralph (a colored man), on Habeas Corpus.”

The legal question was whether Jordan Montgomery had a legitimate claim to demand Ralph’s return. Jordan Montgomery’s lawyers argued when Ralph relocated to the Iowa Territory, slavery was not specifically prohibited in Iowa under the so-called Missouri Compromise of 1820, since a local legislature had not taken additional action to ban it. Jordan Montgomery’s lawyers also claimed Ralph was a fugitive slave, since he had failed to fulfill his contract and should be returned to Missouri under conditions of the federal Fugitive Slave Act.

Ralph Montgomery’s attorney, David Rorer, argued that Ralph became a free man when, by consent of his master, Ralph moved to Iowa. Rorer, and rising star in the Iowa Territory, claimed that his client was neither a slave nor a fugitive, in part because he entered a contract “which presupposes a state of freedom.” Rorer also cited an English case in which it was ruled that a slave having lived in a free country could not be taken to another land that would again lead him into slavery. According to Rorer, the only obligation Ralph owed was to raise the $550 for his former owner in Missouri.

Rorer also cited Chapter 23 of the Book of Deuteronomy in the Bible, which says, in part: “Thou shalt not deliver unto his master the servant which is escaped from his master unto thee: He shall dwell with thee, even among you.”

Ruling delivered on Independence Day 1839

The Iowa Supreme Court conceded Ralph Montgomery should repay Jordan Montgomery — with one key stipulation. “It is a debt which he ought to pay, but for the non-payment of which no man in this territory can be reduced to slavery,” wrote Charles Mason, the first chief justice of the Iowa Supreme Court.

Mason concluded Ralph Montgomery “should be discharged from all custody and constraint, and be permitted to go free while he remains under the protection of our laws.” The Iowa Supreme Court declared Ralph Montgomery a free man on Independence Day, July 4, 1839.

In their opinion, the court justices wrote, “When, in seeking to accomplish his object, (the claimant) illegally restrains a human being of his liberty, it is proper that the laws, which should extend equal protection to men of all colors and conditions, should” intervene.

The unanimous ruling established the tradition in Iowa’s courts of ensuring the rights and liberties of all the people of the state. Years later, the state legislature adopted Iowa’s motto: “Our liberties we prize and our rights we will maintain,” which stands as a permanent reminder that the freedoms in this state are freedoms for all.

What happened to Ralph?

Ralph Montgomery remained in Iowa for the rest of his life. According to the State Historical Society of Iowa, he showed up one day to work in Judge Wilson’s garden in 1840 (one year after the Iowa Supreme Court ruling in his favor). “I ain’t paying you for what you done for me,” Ralph said. “But I want to work for you one day every spring to show you that I never forget.”

Ralph Montgomery stayed in Dubuque the rest of his life, a free man. While not much is known about how he lived the remainder of his life, we do know he continued to mine lead and was a familiar figure around town. While the Dubuque Times in 1870 credited Ralph Montgomery with finding several valuable lodes, he eventually fell in hard times, either through being swindled or by gambling, according to conflicting accounts. During his later years, he lived in the county poor house, according to the Dubuque Times. He succumbed to smallpox, a disease he contracted while nursing a sick patient, during his time in Dubuque’s pest house. He died on July 23, 1870.

(A pest house, short for pestilence house, was a quarantine facility typically found throughout American communities in the late 1800s. Before the development of hospitals, people afflicted with communicable diseases such as tuberculosis, cholera, smallpox or typhus were placed in pest houses.)

Ralph was buried in the city cemetery which became in Jackson Park in later years, according to Encyclopedia Dubuque. When that cemetery was closed, Ralph’s remains were among those moved to Linwood Cemetery, where they were buried in a mass grave.

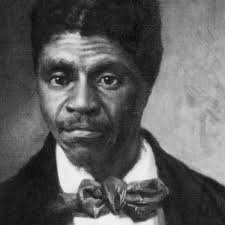

Ralph Montgomery’s case offered much different outcome than Dred Scott case

Eighteen years later, the lessons of Ralph Montgomery’s case seemed to be forgotten when Missouri slave Dred Scott pleaded his case for freedom in court. On March 6, 1857, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its decision on Sanford v. Dred Scott, a case that intensified national divisions over the issue of slavery.

In 1834, Dred Scott, a slave, had been taken to Illinois, a free state, and then to the Wisconsin Territory, an area where the Missouri Compromise of 1820 prohibited slavery. Scott lived in Wisconsin with his master, Dr. John Emerson, for several years before returning to Missouri, a slave state. In 1846, after Emerson died, Scott sued his master’s widow for his freedom on the grounds that he had lived as a resident of a free state and territory. He won his suit in a lower court, but the Missouri Supreme Court reversed the decision.

Dred Scott

Scott appealed the decision. A federal court decided to hear the case on the basis of the diversity of state citizenship represented. After a federal district court decided against Scott, the case came on appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, which was divided along slavery and antislavery lines; although the Southern justices had a majority.

During the trial, the antislavery justices used the case to defend the constitutionality of the Missouri Compromise, which had been repealed by the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. The Southern majority responded by ruling on March 6, 1857, that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional and that Congress had no power to prohibit slavery in the territories. Three of the Southern justices also held that African Americans who were slaves or whose ancestors were slaves were not entitled to the rights of a federal citizen, and therefore had no standing in court.

These rulings all confirmed that, in the view of the nation’s highest court, under no condition did Dred Scott have the legal right to request his freedom. The Supreme Court’s verdict further inflamed the irrepressible differences in America over the issue of slavery, which in 1861 erupted with the outbreak of the American Civil War.

Shattering Silence

It would take the Civil War, the passage of the 13th Amendment to abolish slavery and the civil rights’ movement of the mid-20th century to help create a more just America for everyone, regardless of race. The battle is not yet over, as evidenced by the Black Lives Matter movement, police brutality (in tragic cases such as the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis in late May 2020) and the resulting civil unrest that has swept America.

Shattering Silence in Des Moines near Iowa Supreme Court (photo from Des Moines Public Art Foundation)

Even as racial-charged protests turned into riots in downtown Des Moines during the weekend of May 30-31, a 30-foot sculpture near the Iowa Supreme Court pointed to the hope that has endured in Iowa from the beginning.

“Shattering Silence,” which features a ring made of limestone quarried in Dubuque, was designed by artist James Ellwanger and installed in 2009 on the 170th anniversary of the Iowa Territory Supreme Court’s landmark decision in the Ralph Montgomery case. (Photo credit for the winter image of Shattering Silence that I used with this post goes to Jason Mrachnia.)

The stunning sculpture stands at the top of the hill overlooking the Des Moines skyline. The Iowa Art Council has called the piece a commemoration of “those moments when Iowa has been at the forefront of breaking the silence of inequality and commemorates those Iowans who refused to stand by silently when they saw injustice.”

Former slave who made history in Iowa leaves powerful legacy

Back in Dubuque, local residents raised money in recent years to install a tombstone to honor Ralph Montgomery. On October 1, 2016, community leaders unveiled a monument to Ralph in the Linwood Cemetery to highlight Iowa’s ongoing role in shattering the silence on the issue of racial inequality.

“We are gathered today to honor a man who has brought such honor to this state by helping us discover not only who we were at that time, but who we would hope to become today,” said Mark Cady, former chief justice of the Iowa Supreme Court who passed away in November 2019. “Ralph Montgomery suffered through the indignity of slavery to rise and stand against it and help forge a great meaning …of our collective belief in equality, both then and now.”

Want more?

I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you value intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, agriculture updates, recipes and tips to make you a better communicator.

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press. Also take a look at my other books, including “Iowa Agriculture: A History of Farming, Family and Food” from The History Press, “Dallas County” and “Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing. All are filled with vintage photos and compelling stories that showcase the history of small-town and rural Iowa. Click here to order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page, or click here. Feel free to share this with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

Also, if you or someone you know could use my writing services (I’m not only Iowa’s storyteller, but a professionally-trained journalist with 20 years of experience), let’s talk. I work with businesses and organizations within Iowa and across the country to unleash the power of great storytelling to define their brand and connect with their audience through clear, compelling blog posts, articles, news releases, feature stories, newsletter articles, social media, video scripts, and photography. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com, or e-mail me at yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com, and yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Talk to you soon!

The Corn Lady: Jessie Field Shambaugh and the Birth of 4-H in Iowa

Well-behaved women rarely make history. At a time when young girls in rural Iowa generally weren’t encouraged to broaden their knowledge of agriculture, Jessie (Field) Shambaugh chose to attend educational farm meetings with her father by the time she was 12 years old. She went on to become one of the first female ag teachers in the nation. By the time she was 24, she was elected superintendent of schools for Page County, Iowa. “The Corn Lady,” as she was affectionately known, also helped guide the formation of an innovative new learning opportunity that endures today–4-H–with the goal to “make the best better.”

Farm women have long broken new ground in rural Iowa. Jessie Field Shambaugh (sister of the famous nursery and garden innovator Henry Field) guided the formation of today’s 4-H clubs during her tenure as a country schoolteacher in southwest Iowa.

Born in 1881 on a farm near Shenandoah, Shambaugh started her career teaching taught country school in southwest Iowa. By the turn of the twentieth century, “Miss Jessie” was a woman far ahead of her time. An innovative teacher, she introduced basic science classes in addition to the “3 Rs” in the country school curriculum. She believed in teaching country children in terms of country life and was a strong proponent of relating school lessons more closely to life on the farm and in the rural home.

Jessie Field Shambaugh of Iowa

By developing the Boys’ Corn Club and the Girls’ Home Club, Miss Jessie created the forerunner of 4-H and became the first female ag teacher in the nation. Her knowledge of agriculture was extensive, as her father had encouraged her to learn about farming methods from the time she was a young girl. As early as age twelve, Miss Jessie attended local Farmers’ Institute meetings with her father and listened to presentations from ag leaders like “Uncle Henry” Wallace, who edited Wallaces’ Farmer.

Inspired by these ideas, Miss Jessie promoted hands-on, practical learning. She pioneered a powerful educational concept to help young people learn “to make the best better.” By age twenty-four, Miss Jessie had been elected superintendent of schools for Page County. She was one of the first female county superintendents in Iowa.

Starting in 1906, she enlisted the assistance of the 130 one-room country schools in the county to form boys’ and girls’ clubs. Miss Jessie encouraged the young people to participate in judging contests. She believed that friendly competition inspired students to excel. At the Junior Exhibits held at the Farmers’ Institute in Clarinda, entry classes for students included “Best 10 Ears of Yellow Dent Corn,” “Best Device Made by a Boy for Use on the Farm” and “Best 10 Ears of Seed Corn Selected by a Girl.”

Miss Jessie’s efforts gained national attention from educators and reporters. She hosted the U.S. Commissioner of Education and state superintendents as they toured Page County clubs in 1909. She designed the 3-leaf clover pin to reward 3-H project winners and wrote the Country Girls Creed. Jessie Field Shambaugh’s vision and pioneer spirit led to 4-H clubs nationwide, notes the Iowa 4-H Foundation.

4H logo

The goal was to “make the country life as rewarding as it might be in any other walk of life,” Miss Jessie noted in The Very Beginnings. While she passed away at age 90 in 1971, Shambaugh was inducted into the Iowa Women’s Hall of Fame in 1977, and her legacy lives on.

“My mother always wanted to help the farm boys and girls,” said Miss Jessie’s daughter, Ruth Watkins of Clarinda, whom I interviewed in 2002. “She had great idealism and was able to carry it through to reality.”

This is the spirit that inspired me to post this on March 8–International Women’s Day (IWD). I’ve long been inspired by rural Iowa women like Miss Jessie, who were breaking new ground as they became a force for good in their local community, long before the first IWD, which dates back to 1911. I think Miss Jessie would agree with the IWD’s philosophy that “We are all parts of a whole. Our individual actions, conversations, behaviors and mindsets can have an impact on our larger society.”

Want more?

Thanks for stopping by. Miss Jessie’s story is just one of the remarkable women featured in Chapter 9, “Iowa Women Blaze New Trails in Agriculture,” in my upcoming book Iowa Agriculture: A History of Farming, Family and Food, which will be release on April 27, 2020, by The History Press.

In the meantime, I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you value intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, agriculture updates, recipes and tips to make you a better

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press. Also take a look at my latest book, “Dallas County,” and my “Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing. Both are filled with vintage photos and compelling stories that showcase he history of small-town and rural Iowa. Order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page, or click here. Feel free to share this with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

Also, if you or someone you know could use my writing services (I’m not only Iowa’s storyteller, but a professionally-trained journalist with 20 years of experience), let’s talk. I work with businesses and organizations within Iowa and across the country to unleash the power of great storytelling to define their brand and connect with their audience through clear, compelling blog posts, articles, news releases, feature stories, newsletter articles, social media, video scripts, and photography. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com, or e-mail me at yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com, and yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Talk to you soon!

Darcy

When Agriculture Entered the Long Depression in the Early 1920s

The culture of Iowa agriculture hasn’t only been shaped by good times. The farm crisis that started in the 1920s, a decade before the Great Depression engulfed America, shook rural Iowa to its core. In the post–World War I era, the Golden Age of Agriculture was over, and farmers throughout the Midwest began to suffer the effects of an increasing economic depression that culminated at the close of the 1920s with the stock market crash.

“To understand the nature of the agricultural problem more clearly, it needs to be said that farming is a difficult and uncertain profession,” noted Gary D. Dixon in his thesis “Harrison County, Iowa: Aspects of Life from 1920 to 1930,” which he presented in 1997 to the Department of History to earn his Master of Arts degree from the University of Nebraska–Omaha. “The farmer has no control over the prices he pays for goods or, more importantly, for what he can ask for his own products, as he ‘buys in a seller’s market, and he sells in a buyer’s market.”

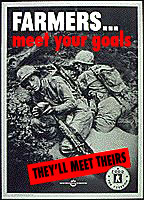

Wesells Living History Farm WW1

It was definitely a seller’s market during World War I, when all sectors of the American economy produced as much as possible to help the war effort. It was profitable, as well as patriotic, to raise crops at top capacity. But then the war ended on November 11, 1918.

“Government price supports for agriculture were kept through 1920, when the guaranteed prices on wheat and other crops were terminated,” Dixon noted. “The government ended loans to European nations at the same time, which meant they were unable to purchase U.S. agricultural products.”

This is what had kept the exports going, and exports had driven the boom in the U.S. farm economy. In the years just after World War I, prices for farm goods fell by half, as did farmer income. The Federal Reserve raised the credit rate just when the farmer needed its help the most, so money tightened up. Banks did not renew notes, but mortgages and bills still came due. To make it worse, the railroads raised their freight rates, so it was more expensive to get the crops to market, Dixon noted.

Farm income fell from $17.7 billion in 1919 to $10.5 million in 1921—nearly a 41 percent drop. In Iowa, farm values that had almost tripled between 1910 and 1920 plunged during the 1920s. In Harrison County in southwest Iowa, 1930 land values of $41 million reflected a drop of more than $35 million from 1920, Dixon said. In addition, Harrison County’s total crop values, which in 1919 were more than $10.8 million, fell to roughly $5.7 million by 1924. “Taxes on the remaining income, and the other expenses incurred in farming, remained as high as they ever were, or increased,” Dixon added.

While there had been a historic growth in the number and size of farms in the nation until 1920, that soon changed. Then the farm population showed net losses of 478,000 in 1922 and 234,000 in 1923. The more lucrative prospects of the city lured many of the best of the younger generations away, Dixon said.

Iowa farm, 1920s Source: Library of Congress

Banding Together in Farmer Cooperatives

In response to these troubling developments, some farmers began organizing with their neighbors so their shared concerns could be heard at the county, state and national level. Some turned to groups like the Iowa Farmers Union, which had formed in 1915 to help members work together to strengthen the independent family farm through education, legislation and cooperation.

Others turned to a new group, the Iowa Farm Bureau Federation (IFBF), which had formed on December 27, 1918, during a meeting in Marshalltown. The sSeventy-two county Farm Bureau groups from across Iowa voted unanimously during this meeting to form a state federation. These farmers knew that they needed a stronger voice in legislation governing their industry, improved marketing for their ag products and better relationships with other related industries, including meatpackers and the railroads.

“We regard this movement as one of the most sensible efforts toward an organization of farmers that has yet been made,” said Henry A. Wallace, the editor of Wallaces’ Farmer, who went on to become U.S. secretary of agriculture and vice president of the United States.

The IFBF also helped support the cooperative marketing movement that had been gaining momentum, noted Tim Neiss, IFBF historian. Ag cooperatives had started to form in Iowa by the mid-1800s in response to unfair business practices by the railroads that hurt competition and lowered the prices farmers received for their products. Farmers began banding together to market their products more efficiently, at higher prices, as well as to buy inputs at lower cost.

One of these early Iowa cooperatives was Farmers Cooperative Elevator of Marcus, which was incorporated on December 12, 1887. The Marcus location, which is now part of First Cooperative Association based in Cherokee, remains the oldest active cooperative elevator in the nation.

While organizing into farm organizations and cooperatives appealed to some farmers, other farmers decided to move in a much more radical direction—one of that would culminate in the Farmers Holiday movement and the near-lynching of an Iowa judge in Le Mars. Get the whole story in my book Iowa Agriculture: A History of Farming, Family and Food, which is published by The History Press the week of April 27, 2020.

Want more?

Thanks for stopping by. I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you value intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, agriculture updates, recipes and tips to make you a better

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press. Also take a look at my latest book, “Dallas County,” and my “Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing. Both are filled with vintage photos and compelling stories that showcase he history of small-town and rural Iowa. Order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page, or click here. Feel free to share this with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

Also, if you or someone you know could use my writing services (I’m not only Iowa’s storyteller, but a professionally-trained journalist with 20 years of experience), let’s talk. I work with businesses and organizations within Iowa and across the country to unleash the power of great storytelling to define their brand and connect with their audience through clear, compelling blog posts, articles, news releases, feature stories, newsletter articles, social media, video scripts, and photography. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com, or e-mail me at yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com, and yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Talk to you soon!

Darcy

Iowa’s “Peacemaker Pig” Floyd of Rosedale Helped Calm Racial Tensions

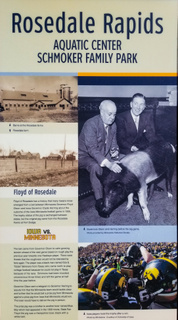

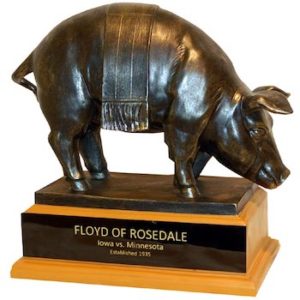

If you follow college football in the Midwest, especially if you’re a University of Iowa Hawkeye football fan, you may know the story of Floyd of Rosedale. A bronze statue of the pig, Floyd of Rosedale, is exchanged between the two states. The original pig himself came from Rosedale Farms at Fort Dodge in north-central Iowa.

The whole deal emerged from a bet between Iowa Governor Clyde Herring and Minnesota Governor Floyd Olson about the outcome of the 1935 Iowa-Minnesota football game, but this story involves something much deeper than a famous pig and a bronze trophy.

The problem started the previous year, on Saturday, October 27, 1934, when rough play was directed towards one Iowa Hawkeye running back, Ozzie Simmons. Simmons was a rarity in that era: a black player on a major college football team. Dubbed the “ebony eel” by some sportswriters of the era, Simmons had come north to play football when he wasn’t allowed to play football in his home state of Texas, due to his race.

America in the 1930s included Jim Crow laws in southern states, which segregated blacks from whites. In northern states, no such laws existed, but discrimination was still widespread.

Simmons’ talent couldn’t be denied, however, and he attracted the attention of a young Iowa sports broadcaster perched high above the field. That broadcaster, who would become President Ronald Reagan, became an Ozzie Simmons fan, noted Minnesota Public Radio (MPR), which aired the story “The Origin of Floyd of Rosedale” in 2005. Reagan described a trademark Simmons’ move during a telephone interview with legendary Iowa sports broadcaster Jim Zabel of WHO Radio in Des Moines.

“Ozzie would come up to a man, and instead of a stiff-arm or sidestep or something, Ozzie — holding the football in one hand — would stick the football out,” Reagan said. “And the defensive man just instinctively would grab at the ball. Ozzie would pull it away from him and go around him.”

There were no dazzling runs against Minnesota, however, in the 1934 game at Iowa. Simmons was knocked out three times, leaving the game for good by halftime. The Gophers overwhelmed Simmons and the rest of the Iowa team, beating them 48-12.

While Minnesota went on to win the national championship that year, Iowa fans at the game were outraged by how Minnesota played, in Iowa City claiming the defense deliberately went after Iowa Simmons hard. (Just 11 years earlier, Iowa State’s first black athlete, Jack Trice, died of injuries sustained in a game at Minnesota in 1923.)

How Floyd of Rosedale was born

In 1935, the Rosedale Trophy debuted in an attempt to generate some goodwill between the two schools. Ahead of the 1935 game, Herring warned Minnesota not to pull the same stunts it did the year before. “If the officials stand for any rough tactics like Minnesota used last year, I’m sure the crowd won’t,” Herring said.

Olson sent a telegram to Governor Herring to assure him that the Minnesota team would tackle clean. To help calm the growing tension ahead of the next Minnesota-Iowa football game, Olson also went on to say that he would bet a prize pig from Minnesota against a prize pig from Iowa that Minnesota would win the big game. The loser would have to deliver the pig in person.

“Dear Clyde,” stated Olson’s telegram to Herring. “Minnesota folks are excited over your statement about the Iowa crowd lynching the Minnesota football team. If you seriously think Iowa has any chance to win, I will bet you a Minnesota prize hog against an Iowa prize hog that Minnesota wins today.”

The Iowa governor accepted, and what became known as the Floyd of Rosedale prize was born. Herring apparently followed Olson’s cue. He joked it would be hard to find a prize hog in Minnesota, since they all were so “scrawny.”

Floyd of Rosedale trophy

Word of the bet reached Iowa City as the crowd gathered at the stadium. Things calmed down, and the game proceeded without incident. Minnesota won 13-7.

The prize pig from Iowa was a Hampshire boar, black with a white belt. He was later named the Floyd of Rosedale after Minnesota’s governor. In the week following the big game, Herring delivered the live pig to the Minnesota Capitol building in St. Paul and took Floyd inside to meet Olson.

After the hog’s trophy days were over, Floyd spent his remaining days on a farm in southeast Minnesota. Floyd died of hog cholera in July 1936, about eight months after he made the front page. The real Floyd, Governor Olson, passed away less than a month later, dying of cancer in August 1936.

(Ironically, Floyd the hog wasn’t the only celebrity in his family. Floyd of Rosedale was the brother of another famous boar, Blue Boy, who had appeared in the 1933 movie “State Fair.”)

Leaving a legacy

All these years later, the famous Floyd of Rosedale endures as one of college football’s most famous trophies. Floyd of Rosedale’s legacy is also preserved in a marker by the Rosedale Rapids Aquatic Center in Fort Dodge.

Simmons, whose story prompted the Floyd of Rosedale trophy, never took much interest in the trophy, in part because of the era of racial discrimination it recalled. He was denied a chance to play professional football, because the National Football League banned black players at the time, noted MPR. He played some minor league ball, joined the Navy and eventually became a Chicago public school teacher.

“When Ozzie Simmons stepped onto the field in October, 1934, to play Minnesota, he entered a national drama that’s still playing out today,” MPR noted. “All Simmons wanted was a chance. The trophy is an ever-present reminder of how precious that right is.”

Want more stories like this?

These are the kinds of stories I’m sharing in my new book, “Iowa Agriculture: A History of Farming, Family and Food,” which was released by The History Press on Monday, April 27, 2020. Order your signed copy by clicking here to my online store.

One more thing–the story of illegal gambling

After I posted this story, I received this intriguing email from my friend Victoria Herring of Des Moines:

“You may remember coming to Artisan Gallery 218 to do book talks. I was reading your website about the Floyd of Rosedale story – apparently appearing in an upcoming book. I assume you know there’s a bit more to the story == I think George Mills wrote about it in one of his books == when this happened some guy [whose name I forget but he was a bit of a thorn in the side of some public figures] filed a criminal complaint against Gov. Herring [he was my grandfather] alleging illegal betting — might be an interesting even if a little off topic addition.”

I pulled out a copy of George Mills’ classic book, Looking in Windows: Surprising Stories of Old Des Moines, and saw exactly what Victoria was talking about. In the second called “A Governor Arrested,” Mills explained how a gadfly named Virgil Case in Des Moines got a warrant for Governor Herring’s arrest following the Floyd of Rosedale 1935 bet. The charge? Gambling on a hog wager.

At the time, Iowa law provided a penalty of up to a $100 fine or 30 days in jail for gambling. Municipal Judge J.E. Mershon signed the warrant.

Who was Case and why did he go to all this trouble? He was a “natural-born hell raiser,” wrote Mils, who added that Case had been a secretary to a Des Moines mayor and publisher of a weekly newspaper.

Case explained how he happened to file the charge. He said he had some spare time, and it occurred to him a “good way to put in that time was to go over to Municipal Court and have the governor arrested. So that’s what I did.” He said his profession was “raising hell with public officials because they should be the first to set a good example.”

Word of the warrant reached Herring while he was still with Minnesota Governor Olson in Minneapolis. Herring immediately engaged Olson as his attorney. Olson squelched a suggestion that the pig be auctioned off to pay a possible Herring fine. “That pig stays in Minnesota, regardless of what happens,” Olson declared. He added that the bet wasn’t a gamble anyway, since Minnesota was a cinch to win the game.

Olson suggested that Herring stay in St. Paul, where he couldn’t be extradited, since the Minnesota governor had to consent to the extradition, and Olson was already Herring’s attorney. Herring observed that only the governor of Iowa could extradite anyone back to Iowa–and he was the governor of Iowa.

“Olson added a sly insult when he said it wasn’t gambling because ‘nothing of value was involved,'” Mills wrote. Herring shot back that Floyd of Rosedale was a “right good hog.”

Walter Brick, deputy municipal court bailiff, cause a stir of excitement at the Iowa statehouse a few days later. When he showed up at Herring’s office, reporters thought maybe he was there to lead the governor away in handcuffs. Nope. Brick just wanted to talk over a planned court hearing on the charge.

The only action the deputy took that day was to join the reporters in eating apples out of Herring’s fruit basket. (“Beside apples, Herring was known at times to shut the door and provide the press with beer and Pella bologna, something no governor has done since,” Mills wrote.)

In the hearing, reporters and others testified that Herring hadn’t committed the so-called offense in Des Moines, that the bet wasn’t complete until Herring and Olson met in Iowa City. Assistant Polk County Attorney C. Edwin Moore, later chief justice of the Iowa Supreme Court, moved that the case be dismissed. Judge Mershon was glad to do so. “The folderol was over,” Mills concluded.

Want more?

Thanks for stopping by. I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you value intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, agriculture updates, recipes and tips to make you a better

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press. Also take a look at my latest book, “Dallas County,” and my “Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing. Both are filled with vintage photos and compelling stories that showcase he history of small-town and rural Iowa. Order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page, or click here. Feel free to share this with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

Also, if you or someone you know could use my writing services (I’m not only Iowa’s storyteller, but a professionally-trained journalist with 20 years of experience), let’s talk. I work with businesses and organizations within Iowa and across the country to unleash the power of great storytelling to define their brand and connect with their audience through clear, compelling blog posts, articles, news releases, feature stories, newsletter articles, social media, video scripts, and photography. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com, or e-mail me at yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com, and yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Talk to you soon!

Darcy

Independence, Iowa’s Connection to the Titanic and Carpathia

It’s amazing how many Iowans have ties to the Titanic, even all these years after the great ship sank. During a program at the Independence Public Library in June 2019, a lady named Ann Gitsch from Independence approached me following the program. As soon as she mentioned she had a relative on the Carpathia who helped rescue Titanic survivors, she had my total attention.

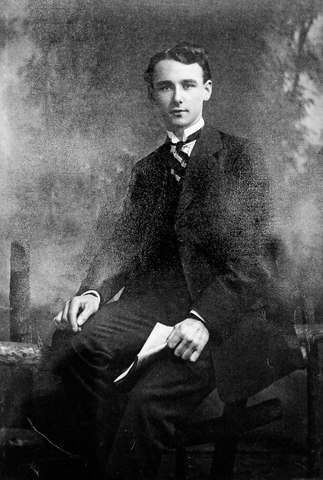

Ann mentioned that her family was from Northumberland in northeast England, and her grandmother, Wynanda Purvis was an aunt to Robbie Purvis, who was a steward on the Carpathia. Robbie Purvis was working on the Carpathia when the steamship rescued passengers from the Titanic during the early morning hours of April 15, 1912.

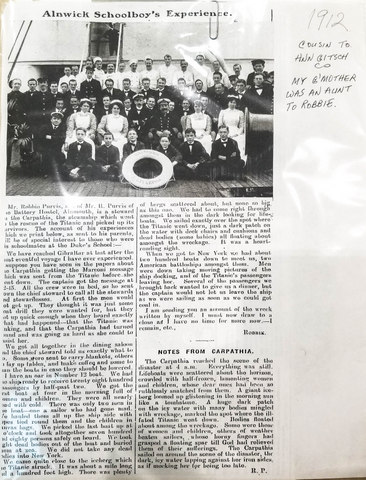

As Gitsch told me about Purvis, she handed me a copy of an unnamed publication with an article titled “Alnwick Schoolboy’s Experience.” (Alnwick is a town in Northumberland, England.)

The following article was taken from a 1912 letter Purvis wrote to his parents, including Mr. R. Purvis of Battery Hostel, Alnmouth, in northern England, following the Titanic disaster. The news article promised to be “of special interest to those were his [Purvis’s] schoolmates at the Duke’s School:”

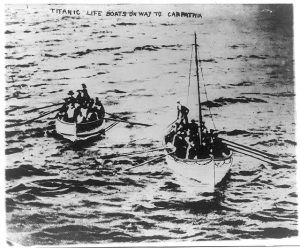

Survivors from the Titanic row towards the Carpathia

We have reached Gibraltar at last after the most eventful voyage I have ever experienced. I suppose you have seen the papers about the Carpathia getting the Marconi message which was sent from the Titanic before she went down. The captain got the message at 12:15. All the crew were in bed, so he sent down the chief steward to call all the stewards and stewardesses. At first the men would not get up. They thought it was just some boat drill they were wanted for, but they got up quick enough when they heard exactly what had happened—that the Titanic was sinking, and that the Carpathia had turned around and was going as hard as she could to assist her.

We got all together in the dining saloon, and the chief steward told us exactly what to do. Some were sent to carry blankets, other to lay up tables and make coffee, and some to man the boats in case they should be lowered.

I have an oar in Number 12 boat. We had the ship ready to receive 2,800 passengers by half past two. We got the first boat [from the Titanic] at 4 in the morning full of women and children. There were all nearly mad with cold. There was only two men in the boat—one a sailor who had gone mad. We hauled them all up the ship’s side with ropes tied around them and the children in canvas bags. We picked the last boat up at ? o’clock [newsprint here was illegible] and took altogether 780 persons safely on board. [Purvis’ count wasn’t quite accurate. Later accounts reported that Carpathia rescued 705 survivors from the Titanic, and rescue efforts were completed by 8:30 a.m. on Monday, April 15, 1912.]

We took eight dead bodies out of the boat and buried them at sea. We did not take any dead bodies into New York.

We came quite close to the iceberg which the Titanic struck. It was about a mile long and 100 feet high. There were plenty of bergs scattered about, but none so big as this one. We had to come right through amongst them in the dark looking for lifeboats. We sailed exactly over the spot where the Titanic went down, just a dark patch on the water with deck chairs and cushions and dead bodies (some babies) all floating about amongst the wreckage. It was a heart-rending sight.

When we got to New York, we had about 200 boats down to meet us, two American battleships amongst them. Men were down taking moving pictures of the ship docking, and of the Titanic’s passengers leaving her [the Carpathia]. Several of the passengers we brought back wanted to give us dinner, but the captain would not let us leave the ship, as we were sailing as soon as we could get coal in.

I am sending you an account of the wreck written by myself. I must now draw to a close, as I have no time for more now. I remain, etc., Robbie

Carpathia rescue ship

Iceberg “glistening in the morning sun like a tombstone”

Printed in this same newspaper, beneath Purvis’s letter, was a small section called “Notes from Carpathia,” which contained more details that Purvis jotted down:

“The Carpathia reached the scene of the disaster at 4 a.m. Everything was still. Lifeboats were scattered about the horizon, crowded with half-frozen, lamenting women and children, whose dear ones had been so ruthlessly snatched from them. A giant iceberg loomed up, glistening in the morning sun like a tombstone. A huge dark patch on the icy water with many bodies mingled with wreckage, marked the spot where the ill-fated Titanic went down.

Bodies floated about among the wreckage. Some were those of women and children, others of weather-beaten sailors, whose horny fingers had grasped a floating spar till God had relieved them of their sufferings. The Carpathia sailed on around the scene of the disaster, the dark, icy water lapping against her iron sides, as if mocking her for being too late.”

Want more?

Thanks for stopping by. I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you value intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, agriculture updates, recipes and tips to make you a better communicator. My new non-fiction book, “Iowa’s Lost History on the Titanic,” will be coming out in 2019. In the meantime, click here to get a taste of the fascinating stories you’ll find in this book.

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press. Also take a look at my latest book, “Dallas County,” and my Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing. Both are filled with vintage photos and compelling stories that showcase he history of small-town and rural Iowa. Order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page, or click here. Feel free to share this with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

Also, if you or someone you know could use my writing services (I’m not only Iowa’s storyteller, but a professionally-trained journalist with 20 years of experience), let’s talk. I work with businesses and organizations within Iowa and across the country to unleash the power of great storytelling to define their brand and connect with their audience through clear, compelling blog posts, articles, news releases, feature stories, newsletter articles, social media, video scripts, and photography. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com, or e-mail me at yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com, and yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Talk to you soon!

Darcy

1912 news clipping sharing Robbie Purvis’ Titanic story

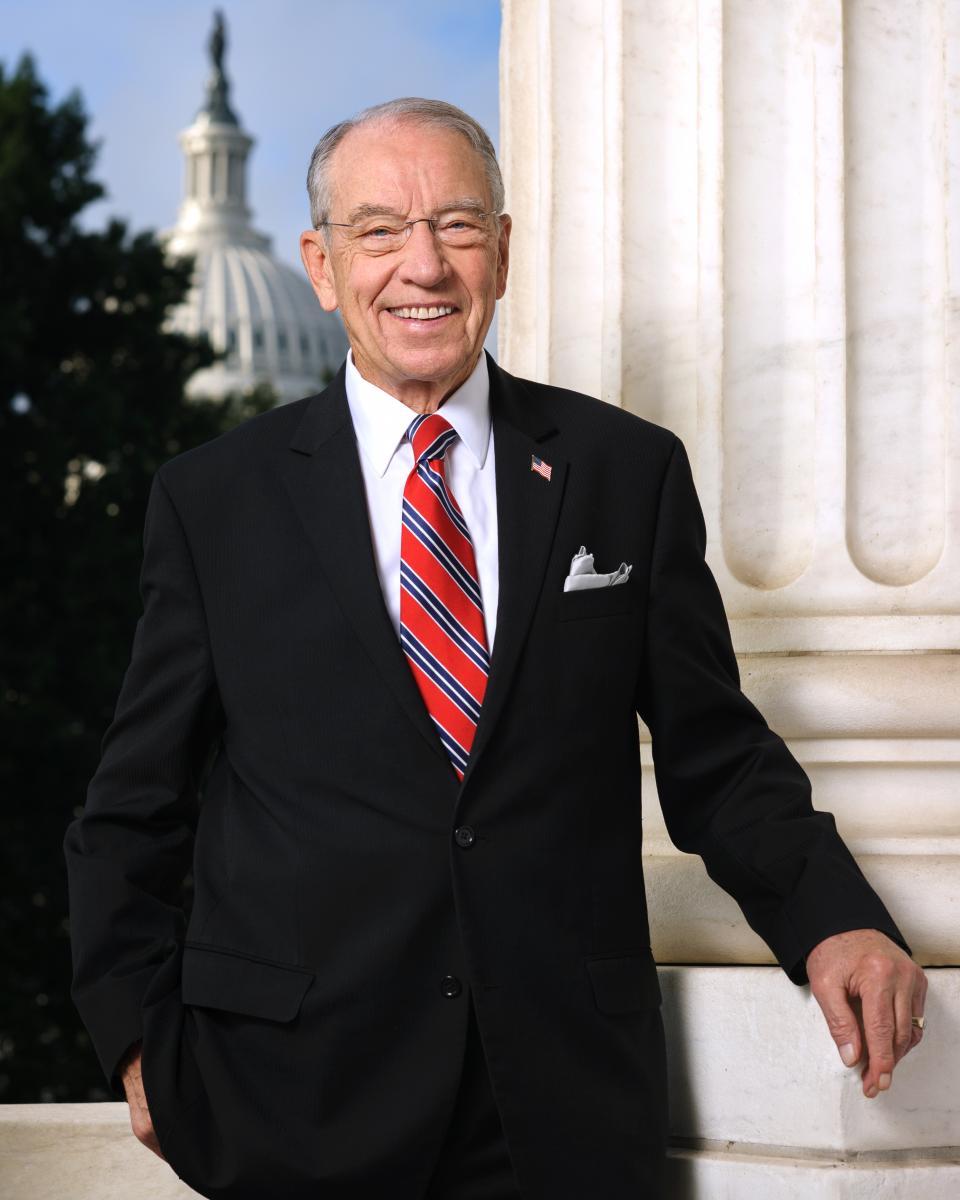

Senator Grassley on Farming: Any Society is Only Nine Meals Away From a Revolution

When people ask about my latest book project and I tell them about Iowa’s Ag History, I get two reactions: either a blank stare, or “Oh cool!” When I reached out to Iowa Senator Charles Grassley, a farmer, to share a few comments for the book, I received more than an enthusiastic response.

I got an incredible interview from a senator who was willing to offer a significant portion of his time to share his insights into the importance of history, agriculture and rural Iowa’s role in the modern global economy. Read on to see why Sen. Grassley says, “I like to remind policymakers that any society is only nine meals away from a revolution.”

When did your family start farming in Iowa?

I am the second generation farmer in my family, following in the footsteps of my father Louis Grassley. His dad emigrated from Germany and died when my dad was just seven years old. At around age 18, my dad started working as a hired hand for the Heitland family on a farm in Hardin County. A few years later, he rented some land near New Hartford in Butler County. In 1927, he and my mother Ruth purchased their own parcel of land.

After graduating from high school, I worked in factories, attended college and farmed with my dad. In 1958, while running for the Iowa legislature and working towards my doctorate at the University of Iowa, I started farming my own piece of the family farm. When my dad passed away in 1960, I rented his 80 acres and about five years later, purchased 120 acres on my own.

When I started out, I grew a bit of everything like most farmers at the time. I grew corn, soybeans, oats and alfalfa and raised sheep, cattle and hogs. My son Robin Grassley, a third-generation farmer, and I continue farming 750 acres together. He rents and owns other farmland along with my grandson Pat Grassley, who is a fourth-generation family farmer.

Barbara and I raised our five children together on our farm near New Hartford, and we enjoy passing on our agrarian heritage and celebrate family gatherings here with our grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

In politics as in farming, a solid understanding of the past is vital to understand current issues. From your unique viewpoint as a senator and a farmer, what’s your take about why it’s important to be well-versed in history–and what are the perils of not knowing history?

As a lifelong farmer who also has worked for six decades representing Iowans in state and federal government, I wear my rural roots as a badge of honor and believe it’s important for farmers to have a seat at the policy-making tables. Farmers take the long view of things, and maybe that’s why they don’t forget important lessons from history.

Only two percent of the American population shoulders the responsibility for growing enough food to feed the U.S. population. Our agrarian-based heritage has experienced rapid transformation in the last generation. Fewer Americans, even in Iowa, have a direct link to living or working on a farm. And most likely due to the affordable abundance of food, not enough people appreciate that food security is directly tied to national security. Food security extends beyond national sovereignty. American agriculture – and the farmers, workers and businesses along the supply chain – anchors the U.S. economy and increasingly strengthens U.S. energy independence, as well.

From a historical perspective, there are two rules of thumb I use to explain how important food security is to maintain peace and prosperity in society. As Emperor of France in the early 19th century, Napoleon Bonaparte reportedly said “to be effective, an army relies on good and plentiful food.” In other words, an army marches on its stomach. Food security ensures a nation can feed its military, whose men and women in uniform are deployed to protect and defend a nation’s sovereignty, at home and abroad. I also like to remind policymakers that any society is only nine meals away from a revolution.

Political leaders who embrace the misguided notion that socialism is the answer to peace and prosperity are either grossly misinformed or willfully ignorant about the peril of leaders who promise to fix “inequality” with government control. Just look at the economic crisis in Venezuela, once one of the most prosperous nations in the Western Hemisphere. The poverty and humanitarian crisis falls squarely in the hands of the nation’s authoritarian regime and its ideologically driven policies. History teaches us that when government suppresses freedom and liberty, the people’s path towards peace and prosperity is replaced with food and medicine shortages, hyperinflation, power outages and even more economic and social inequality.