Iowa’s Vigilante Crime Fighters of the 1920s and 1930s

Who were these guys? It’s a question I couldn’t get out of my mind after I discovered a black-and-white image in the Calhoun County Museum in Rockwell City that showed a group of well-dressed men in front of the Calhoun County Courthouse. The only identification on the image, which appeared to be from the late 1920s or early 1930s, were the words “Calhoun County Vigilantes,” along with some long-forgotten names of men I suspect were mayors and other leaders in local towns around the county.

A recent trip to the fascinating “Ain’t Misbehavin:’ The World of the Gangster” exhibit at the Hoover Presidential Library and Museum helped me piece together some potential clues about the story behind this photo.

While bank robbers and swindlers are as old as the banking industry itself, crime sprees shifted into high gear during the early twentieth century. As early as 1912, the Iowa Bankers Association (IBA) decried the “epidemic” of bank burglaries sweeping the state. This proved to be only an inkling of what lay ahead, however. By 1920, burglaries and holdups had increased so dramatically that new protective measures had to be taken.

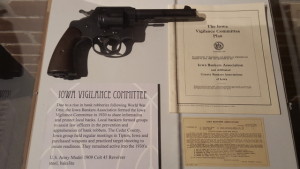

This 2016 display in the “Ain’t Misbehavin:’ The World of the Gangster” exhibit at the Hoover Presidential Library and Museum in West Branch, Iowa, explains more about vigilantes and the role of the Iowa Bankers Association.had increased so dramatically that new protective measures had to be taken.

Although the Iowa Bankers Association (IBA) had previously employed the services of the Pinkerton Detective Agency and the W. J. Burns Detective Agency, the IBA formed Vigilante Committees in the early 1920s to fight the crime wave. In 1921, IBA helped organize 99 county associations and a Vigilance Committee in nearly every city and town in the state to help protect Iowa’s banks.

Vigilantes attracted international attention

The system was a modern reincarnation of the vigilante groups who fought back against horse thieving and cattle rustling during the days of the pioneers. In Iowa, each Vigilance Committee consisted of at least four men in every town where there was a bank. Each committee member was appointed as a deputy sheriff by the county sheriff. In addition, the banks of each county subscribed to at least a $1,000 reward for the apprehension and conviction of bank burglars, plus smaller rewards for telephone operators who helped in the process.

Arrangements were later made with the U.S. War Department so officers in each of Iowa’s County Bankers Associations could purchase guns and ammunition for the members of their Vigilante Committees. The Vigilance Committees were prepared for—and frequently engaged in—gunfights with criminals. At one time, there were 4,303 vigilantes covering 881 banking towns in 84 Iowa counties. “The time of easy dough for the bank bandit has passed,” noted a financial publication that commented on the plan.

Thanks to this system, the bank theft crime wave that had swept Iowa was broken. While losses from bank burglaries totaled more than $225,000 in 1920-1921, more than 100 bank bandits were apprehended from 1920 to 1925. “The plan was such a success that rates for bank burglary and bank insurance in Iowa were dropped to $1 per thousand, while in other states the rates ranged from $4 per thousand in Missouri to $10 per thousand in Oklahoma,” noted Howard E. Bell in his book, “A History of the Iowa Bankers Association.”

Insurance companies across the United States quickly adopted the Iowa Vigilance Committee Plan. A 10 percent discount for both night burglary and daylight holdup insurance rates was automatically granted to banks in any county in the United States that maintained Vigilance Committees.

Iowa’s Vigilance Committee Plan continued to be of national interest for a number of years and generated coverage in a number of magazines and periodicals. As late as 1930, the IBA received an interview request from a publication in Paris, France, that wanted to feature the Vigilance Committee Plan.

IBA takes to the airwaves

Though the vigilantes helped curb crime in the 1920s and early 1930s, the IBA also initiated a low-wave police radio system to bolster its crime prevention efforts. While Des Moines radio station WHO had broadcast news of bank robberies (when requested by the IBA) as early as 1924, it became clear that a radio station devoted solely to police information must be established.

To connect local law enforcement officers with the Iowa Bureau of Criminal Investigation by radio, the IBA purchased a transmitter that was installed in February of 1932 in the organization’s headquarters in the Liberty Building in Des Moines. After the system was tested carefully, station KGHO began regular operations on May 15, 1933.

Later, four other radio stations in Storm Lake, Atlantic, Fairfield and Waterloo (subsequently moved to Cedar Falls) commenced operations to allowed prompt contact with county sheriffs’ offices throughout Iowa. While the IBA transferred the operation of its radio station in 1937 to the State of Iowa and the organization sold its radio equipment, the IBA’s leadership in radio communication helped initiate Iowa’s permanent, statewide police radio system.

Couldn’t resist getting in on the action at the “Ain’t Misbehavin:’ The World of the Gangster” exhibit at the Hoover Presidential Library and Museum in West Branch, Iowa!

Although radio communication lessened the need for Vigilance Committees, the groups continued to function. The rewards that had been offered by various County Associations were rescinded around 1938, however, as the number of bank holdups and burglaries decreased substantially. As new state crime prevention agencies developed, the suggestion was made to abolish the Vigilance Committees, so banks would no longer have to assume the expense of maintaining the committees. Nevertheless, there were 216 vigilantes who remained active in a number of counties across Iowa as late as 1949.

Although the vigilantes and IBA radio stations are long gone, their legacy remains an intriguing part of Iowa history, including right here in Calhoun County.

Explore more rural Iowa history

Like what you’ve seen here? Sign up today for my blog updates and free e-newsletter, or click on the “Subscribe to newsletter” button at the top of my blog homepage.

Want to discover more stories and pictures that showcase the unique history of small-town and rural Iowa? Perhaps you’d like a taste of Iowa’s culture and favorite recipes. Check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa” book from The History Press and “Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing, and order your signed copies today.

Recent Posts

- Do Press Releases Still Work?

- Erasing History? Budget Cuts Threaten to Gut Ag History at Iowa State University

- Machines that Changed America: John Froelich Invents the First Tractor in Iowa

- Bob Feller on Farming, Baseball and Military Service

- Classic Restaurants of Des Moines: A Taste of Thailand Served the "Publics" and Politics

- Want to Combat Fake News? Become a Better Researcher

Categories

- Achitecture

- Agriculture

- Architecture

- baking

- barbeque

- Barn

- breakfast

- Business

- Communication Tips

- Conservation

- content

- cooking

- Crime

- Dallas County

- Economical

- Farm

- Featured

- Food

- Food history

- health

- Iowa

- Iowa food

- Iowa history

- marketing

- Photography

- Recipes

- Seasonal

- Small town

- Storytelling

- Uncategorized

- writing

Archive by year

- 2023

- 2022

- 2021

- 2020

- When Agriculture Entered the Long Depression in the Early 1920s

- The Corn Lady: Jessie Field Shambaugh and the Birth of 4-H in Iowa

- Sauce to Sanitizer: Cookies Food Products Bottles Hand Sanitizer Made with Ethanol

- Myth Busting: No, Your Pork Doesn't Come from China

- Long Live Print Newsletters! 5 Keys to Content Marketing Success

- Shattering Silence: Farmer Helped Slave Find Freedom and Racial Equality in Iowa

- Meet Iowa Farmer James Jordan, Underground Railroad Conductor

- George Washington Carver Rose from Slavery to Ag Scientist

- Remembering the African-American Sioux City Ghosts Fast-Pitch Softball Team

- Want to Combat Fake News? Become a Better Researcher

- Classic Restaurants of Des Moines: A Taste of Thailand Served the "Publics" and Politics

- 2019

- The Untold Story of Iowa’s Ag Drainage Systems

- Stop Rumors Before They Ruin Your Brand

- Finding Your Voice: The Story You Never Knew About "I Have a Dream"

- Warm Up with Homemade Macaroni and Cheese Soup

- Can a True Story Well Told Turn You into a Tom Brady Fan?

- Baking is for Sharing: Best Bread, Grandma Ruby’s Cookies and Other Iowa Favorites

- 4 Key Lessons from Bud Light’s Super Bowl Corn-troversy

- Could Your Story Change Someone’s Life?

- What To Do When the Travel Channel Calls

- Tex-Mex Sloppy Joes and the Magic of Maid-Rite in Iowa

- How Not to Invite Someone to Your Next Event--and 3 Solutions

- We Need FFA: Iowa Ag Secretary Mike Naig Reflects on His FFA Experiences

- From My Kitchen to Yours: Comfort Food, Conversation and Living History Farms

- Smart Marketing Lessons from an Uber Driver--Listen Up!

- Hog Trailers to Humidors: Two New Iowa Convenience Stores Reflect “Waspy’s Way”

- A Dirty Tip to Make Your Social Media Content More Shareable

- Are You on Team Cinnamon Roll?

- Senator Grassley on Farming: Any Society is Only Nine Meals Away From a Revolution

- Why We Should Never Stop Asking Why

- What’s the Scoop? Expanded Wells’ Ice Cream Parlor Offers a Taste of Iowa

- Independence, Iowa’s Connection to the Titanic and Carpathia

- Memories of Carroll County, Iowa, Century Farm Endure

- Iowa's “Peacemaker Pig” Floyd of Rosedale Helped Calm Racial Tensions

- 2018

- How to Cook a Perfect Prime Rib

- How Did We Get So Rude?

- Mmm, Mmm Good: Soup’s on at the Rockwell City Fire Department

- Quit Using “Stupid Language”

- In Praise of Ham and Bean Soup

- Recalling a Most Unconventional—and Life-Changing--FFA Journey

- Events Spark Stories That Help Backcountry Winery Grow in Iowa

- Sac County Barn Quilt Attracts National Attention

- Doing Good, Eating Good at Lytton Town Night

- Young Entrepreneur Grows a Healthy Business in Small-Town Iowa

- Digging Deeper: Volunteers Showcase Thomas Jefferson Gardens in Iowa

- How to Tell Your Community’s Story—with Style!

- DNA Helps Sailor Killed at Pearl Harbor Return to His Family

- It’s Time to Be 20 Again: Take a Road Trip on Historic Highway 20

- The Biggest Reason You Shouldn’t Slash Your Marketing Budget in Tough Times

- Are You Telling a Horror Story of Your Business?

- Pieced Together: Barn Quilt Documentary Features Iowa Stories

- Unwrapping Storytelling Tips from the Candy Bomber

- Barn Helped Inspire Master Craftsman to Create Dobson Pipe Organ Builders

- Butter Sculptures to Christmas Ornaments: Waterloo Boy Tractor Celebrates 100 Years

- Ag-Vocating Worldwide: Top 10 Tips for Sharing Ag’s Story with Consumers

- 2017

- Growing with Grow: Iowa 4-H Leader Guides 100-Year-Old 4-H Club for 50 Years

- High-Octane Achiever: Ethanol Fuels New Driver Tiffany Poen

- Shakespeare Club Maintains 123 Years of Good Taste in Small-Town Iowa

- Iowa’s Ice Queen: Entrepreneur Caroline Fischer’s Legacy Endures at Hotel Julien Dubuque

- Darcy's Bill of Assertive Rights: How to Communicate and Get What You Need

- Celebrating Pi Day in Iowa with Old-Fashioned Chicken Pot Pie

- Cooking with Iowa’s Radio Homemakers

- Top 10 Tips to Find the Right Writer to Tell Your Company’s Stories

- The “No BS” Way to Protect Yourself from Rude, Obnoxious People

- Learning from the Land: 9 Surprising Ways Farmers Make Conservation a Priority

- Leftover Ham? Make This Amazing Crustless Spinach and Ham Quiche

- Iowa’s Lost History from the Titanic

- Coming Soon--"Dallas County," a New Iowa History Book!

- How to Clean a Burned Pan in 6 Simple Steps

- Iowa Beef Booster: Larry Irwin Takes a New Twist on Burgers

- Get Your Grill On: How to Build a Better Burger

- "Thank God It’s Over:" Iowa Veteran Recalls the Final Days of World War 2

- How to Thank Veterans for Their Military Service

- Imagine That! Writers, Put Your Reader Right in the Action

- Remembering Ambassador Branstad’s Legacy from the 1980s Farm Crisis in Iowa

- Busting the Iowa Butter Gang

- Lightner on Leadership: “Everyone Has Something to Give”

- Show Up, Speak Up, Don’t Give Up

- Small - Town Iowa Polo Teams Thrilled Depression - Era Crowd

- Ethanol:Passion by the Gallon

- Cruising Through Forgotten Iowa History on Lincoln Highway

- Why I'm Using a Powerful 500-Year-Old Technology to Make History--And You Can, Too

- 5 Ways a “History Head” Mindset Helps You Think Big

- Behind the Scene at Iowa's Own Market to Market

- Let’s Have an Iowa Potluck with a Side of History!

- Iconic State Fair Architecture: Historic Buildings Reflect Decades of Memories

- Iconic State Fair Architecture- Historic Buildings Reflect Decades of Memories

- Iowa Underground - How Coal Mining Fueled Dallas County's Growth

- Ultra-Local Eating: Jennifer Miller Guides CSA, Iowa Food Cooperative

- The Hotel Pattee and I are Hosting a Party—And You’re Invited!

- Tell Your Story—But How?

- Mediterranean Delights: Iowa Ag Influences Syrian-Lebanese Church Dinner

- 6 Steps for More Effective and Less Confrontational Conversations

- 6 Steps for More Effective and Less Confrontational Conversations!

- 6 Ways to Motivate Yourself to Write—Even When You’re Not in the Mood

- Always Alert-How to Stay Safe in Any Situation

- Does Accuracy Even Matter Anymore?

- Soy Power Shines at Historic Rainbow Bridge

- Free Gifts! (Let’s Talk Listening, Stories and History)

- 2016

- How to Connect with Anyone: Lessons from a Tornado

- Soul Food: Lenten Luncheons Carry on 45-Year Iowa Tradition

- Top 3 Tips for Writing a Must-Read Article

- Darcy's Top 10 Tips to Better Writing

- Top 8 Tips for Building a Successful Freelance Business

- 10 Steps to Better Photos

- Reinventing the Marketer of 2010

- Extreme Writing Makeover

- My Top Social Media Tips for Farmers: REVEALED!

- Honoring the Legacy of Rural Iowa's Greatest Generation

- Iowa's Orphan Train Heritage

- Dedham’s Famous Bologna Turns 100: Kitt Family Offers a Taste of Iowa History

- Iowa Barn Honors Pioneer Stock Farm

- Darcy's Top 10 Tips for Better Photos

- Soup and Small-Town Iowa Spirit

- Savoring the Memories: Van's Café Served Up Comfort Food for Six Decades

- Mayday, Mayday—The Lost History of May Poles and May Baskets in Iowa

- Iowa's Vigilante Crime Fighters of the 1920s and 1930s

- Very Veggie: Iowan's Farm-Fresh Recipes Offer Guilt-Free Eating

- Iowa Public TV's "Market to Market" Features Expedition Yetter, Agri-Tourism, Des Moines Water Works' Lawsuit

- 62 Years and Counting: Calhoun County, Iowa, Families Maintain 4th of July Picnic Tradition

- “A Culinary History of Iowa” Satisfies: Iowa History Journal Book Review

- For the Love of Baking: Lake City's Ellis Family Showcases Favorite Iowa Farm Recipes (Caramel Rolls, Pumpkin Bars and More!)

- Remembering Sept. 11: Iowa Community’s Potluck Honors America

- Talking Iowa Food and Culinary History on Iowa Public Radio

- Talking "Stilettos in the Cornfield," Taxes, Trade and More on CNBC

- FarmHer #RootedinAg Spotlight--FFA Attracts More Women to Careers in Ag

- Rustic Cooking Refined: Iowan Robin Qualy Embraces Global Flavors

- Voice of Reason: Iowa Pork Producer Dave Struthers Offers Top 10 Tips to Speak Up for Ag

- Iowa Eats! Why Radio Iowa, Newspapers and Libraries are Hungry for "A Culinary History of Iowa"

- Iowa Turkeys Carry on National Thanksgiving Tradition

- Riding with Harry: 2016 Presidential Election Reflects Truman's Iowa Revival at 1948 Plowing Match in Dexter

- All Aboard! Rockwell City’s “Depot People” Offer a Taste of Iowa History

- Is This Iowa's Favorite Appetizer?

- O, Christmas Tree! Small Iowa Towns Celebrate with Trees in the Middle of the Street

- Slaves Escaped Through Dallas County on Iowa’s Underground Railroad

- Adel Barn Accents Penoach Winery in Iowa

- Celebrating New Year's Eve in Style at a Classic Iowa Ballroom