Category: Small town

Slaves Escaped Through Dallas County on Iowa’s Underground Railroad

Imagine you’re a fugitive slave on the run in 1850s Iowa. You’ve managed to escape from Missouri and have made it all the way to Dallas County, but your owner and bounty hunters are close behind. If youor the people who are helping you escape on the Underground Railroad—get caught, the consequences are terrifying.

This really happened near the Quaker Divide northeast of Dexter, Iowa, around 160 years ago. It occurred after the federal Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 made it easier for southern slave owners to recovery their property and levied harsher punishments for anyone interfering in the capture of runaway slaves.

I’m going to include the story in my upcoming “Dallas County” book from Arcadia Publishing, which will be released in the summer of 2017. This will be my third book that helps bring Iowa history to life, along with Calhoun County and A Culinary History of Iowa.

Here’s a first-person look into the Underground Railroad in Iowa, as told by those who lived it. This excerpt comes from the “History of the Quaker Divide” by Darius B. Cook, published by the Dexter Sentinel, Dexter, Iowa, 1914. The story of the Underground Railroad documented here was written by Harmon Cook, who shared his personal experiences as one of its conductors:

Running away to freedom

In the days before the Civil War, Dallas County was on the frontier. Slavery was recognized as a product of Missouri. Iowa being a free state naturally proved a highway for the Underground Railroad. John Brown came through the area. The route started from Tabor in Fremont County and crossed diagonally Adair County, striking Summit Grove, where Stuart is now located.

“From there, one line went east down Quaker Divide, and the other crossed the Raccoon River near Redfield, then through Adel. Both lines came together at Des Moines, on to Grinnell to Muscatine and up to Canada. Many times I have seen colored men and women crossing the prairie…slaves running away to freedom.

In the winter of 1859-60, I was going to school to Darius Bowles, and one Friday evening I was told if I wanted to go to Bear Creek, I would not have to walk, if I wanted to drive a carriage and return it Monday morning. I drove the carriage, and in it were two young colored women. They were sisters and from the west border of Missouri. Their master was their father, and they had both been reared in the family.

War was apparent, and their master decided to sell them “down south.” They heard the plotting, and found out that they were to go on the auction block, and made a run for the North Star. They had been on the road seven weeks when they arrived at A.W.L’s at Summit Grove. Before daylight Saturday morning, they were housed at Uncle Martin’s.

You won’t find any slaves here

One Monday afternoon, one of the sisters, Maggie, who had been out in the yard came running in and told grandmother, “Master is coming up the road!” Grandfather went out in the front and sat down in his chair against the side of the door.

By this time, a number of men had ridden up and asked him if he had seen any slaves around. He told them slaves were not known in Iowa.

Then one of them said, “I am told that you are an old Quaker and have been suspected of harboring black folks as they run away to Canada. I have traced two girls across the country, and have reasons to believe they have been here.”

Grandfather said, “I never turn anyone away who wants lodging, but I keep no slaves.”

“Then I’ll come in and see,” said the man, who jumped off his horse and started for the house. Grandfather stood up with his cane in his hand and stepped into the door when the man attempted to enter. Grandfather said, “Has thee a warrant to search my house?”

“No, I have not,” replied the man.

“Then thee cannot do so,” Grandfather said.

“But I will show you,” said the man. “I will search for my girls.”

While this parley was going on, and loud words were coming thick and fast, Grandmother came up and said, “Father, if the man wants to look through the house, let him do so. Thee ought to know he won’t find any slaves here.”

Grandfather turned and started at her a minute, then turning to the men, said, “I ask thy forgiveness for speaking so harshly. Thee can go through the house, if Mother says so.”

Grandfather showed him through all the rooms but stayed close to him all the time. After satisfying himself that they were not there, he begged the old man’s forgiveness, mounted his horse and rode away.

When the coast was clear, it was found that when Maggie and rushed in and said, “Master is coming,” Grandmother hastily snatched off the large feather bed, telling both the girls to get in and lie perfectly still. She took the feather bed, spread it all over them, put on the covers and pillows, patted out the wrinkles—and so—no slaves were seen.

Almost caught

One time a big load was being taken down the south side of the Coon River and had reached the timber on the bluffs near Des Moines. About 3 o’clock in the morning as the carriage was leisurely going along, the sound of distant hoofbeats were heard coming behind. At first it was thought the carriage could outrun its pursuers, but prudence forbade.

A narrow road at one side was hastily followed a few rods, and the carriage stopped. The horseman passed on, swearing eternal vengeance on the whole “caboodle,” if captured. When sounds were lost in the distance, a dash was made for the depot in Des Moines, and all safely landed before daylight.

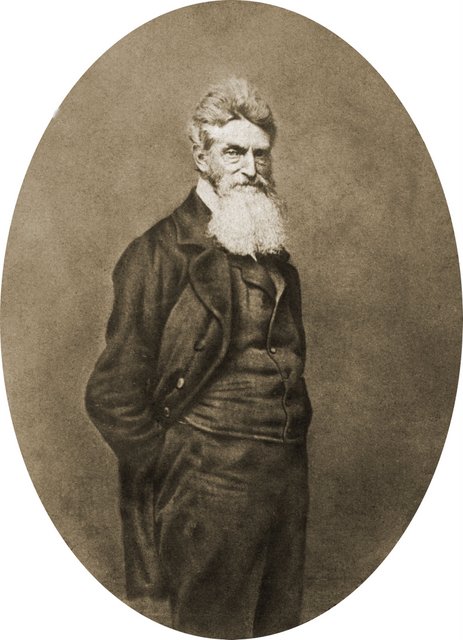

John Brown, abolitionist, aided the Underground Railroad in Dallas County, Iowa

John Brown came to Dallas County

One evening some months after I was returning from Adel on horseback and when opposite Mr. Murry’s farm east of Redfield when I saw Old Man Murry and a stranger back of the barn. I was met by an old man, rather stoop-shouldered and of stern aspect. “Mr. Murry said, “Here’s the youngster who came so near getting caught going to Des Moines.” The stern man with shaggy eyebrows almost in my face said, “Young man, when you are out on the Lord’s business, you must be more discreet. You must always listen backwards, as you are always followed. I’m responsible for that track of the Underground Railroad, and I want my conductors to be more careful in the future, as things are coming to a head, and somebody is going to get hurt.”

I was dismissed with this admonition: “Young man, never do so rash a thing again as to talk and laugh out loud on the way.” A few months later, when Harper’s Ferry was known to fame, I remembered John Brown as the old man at Murry’s.

Editor’s note: In 1859, John Brown led a small group of men who plotted to overthrow the institution of slavery by violent means, starting with a raid on the U.S. arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia. Brown intended to incite a slave insurrection. Although he was suppressed by federal forces, Brown became a martyr in the eyes of the Abolitionist movement. Brown’s unsuccessful raid, along with the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, led Southern states to believe that they could never survive under an anti-slavery president. South Carolina led the Southern states in secession from the Union in December 1860, followed by Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, Florida, Louisiana and Texas.

Reconnecting with a fugitive slave

Harmon Cook continued with his memories of the Underground Railroad in Dallas County:

When I enlisted in Company C, 46th Iowa Infantry, and arrived at Memphis, Tennessee, in 1864, I first saw a regiment of colored soldiers. They were in camp and the first opportunity I was over to see how they looked as soldiers. One of the camp scenes was some of the soldiers conducting a school to teach these poor people their ABCs.

Chaplain Ham and I had gone together, and the teacher, who was the lieutenant colonel, asked us to speak to the colored school. When I had spoken, a strapping fellow in blue uniform came rushing up to me, shouting, “I know you! You belong to the Quaker Divide in Iowa. You drove me one night when we were trying to get into town and were followed by our masters, and you drove off into the woods and we got out and hid.”

It was Henry who had been one of the party in that wild midnight ride. He never got to Canada, but stopped in Wisconsin, and when the war came on he enlisted. He was lieutenant of the colored regiment and was a trusted scout for the general of our division.”

Background notes on the Underground Railroad in Dallas County

The Bear Creek Settlement, also known as the “Quaker divide” in southern Dallas County north of Dexter, is located between the South Raccoon River on the north and Bear Creek on the south.

In the early 1850s this area was open prairie without a single settler. But a Quaker family (including Richard Mendenhall and his wife, Elizabeth) from Marion County, Indiana, settled in Dallas County in 1853 in Union Township in what would become the Quaker Divide.

While the Quakers were among the most prominent slave traders during the early days of America, paradoxically, they were also among the first religious denominations to protest slavery. While not all Quakers participated in the organized anti-slavery movement, many did—including many in Iowa.

Traces of the Underground Railroad remain in Iowa—see for yourself

There are remarkable places across Iowa where you can see the few remaining stops on the Underground Railroad that are still standing and open to the public. I’ve toured many of these remarkable sites, and they are well worth a road trip. Click here to get more details on the Hitchcock House in Lewis, the Jordan House in West Des Moines and the Lewelling House in Salem and more. I encourage you to visit these Underground Railroad sites and reconnect with this powerful chapter of Iowa history.

Want more Iowa culture and history? Check out my top-selling “Calhoun County” book, which showcases the history of small-town and rural Iowa, as well as my “Culinary History of Iowa” book from The History Press. Order your signed copy today!

P.S. Thanks for joining me. I’m glad you’re here.

@Copyright 2017 Darcy Maulsby & Co.

O, Christmas Tree! Small Iowa Towns Celebrate with Trees in the Middle of the Street

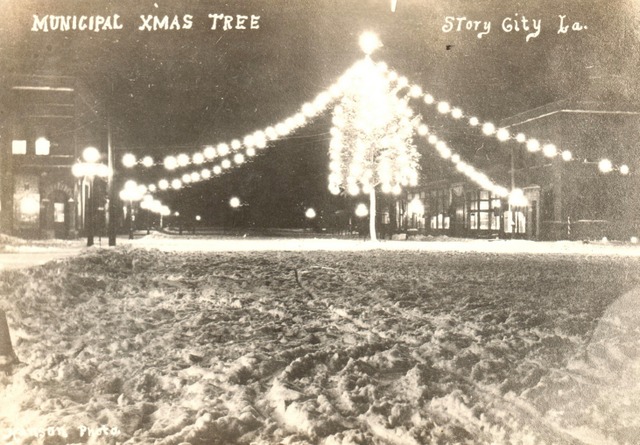

For a select group of small Iowa towns, it just wouldn’t be Christmas without a lighted tree downtown—right in the middle in the street. In Story City, the community has celebrated this beloved holiday custom for more than 100 years.

“I’m not surprised this tradition has lasted all these years,” said Kate Feil, director of the Story City Historical Society. “Keeping traditions alive are a big part of Story City, from the annual Scandinavian Days Festival to the municipal Christmas tree.”

This year’s evergreen tree was donated by Ole and Jackie Skaar of Story City and was installed by the Municipal Electric Company at the corner of Broad Street and Pennsylvania Avenue. Hundreds of people attended the Yulefest tree lighting ceremony on the evening of Nov. 25. Excitement intensified during countdown from 10 to 1 before the lights were flipped on. Then the high school choir led the singing of Christmas carols, and guests could warm up with cups of hot chocolate. The Story City Fire Department hosted their annual chili supper following the tree lighting ceremony.

“Families plan their Thanksgiving gatherings each year so they can attend the tree lighting ceremony,” said Abby Huff, executive director at Story City Greater Chamber Connection. “It’s a tradition we hope to carry on for many more years to come.”

Hundreds of people attended the Yulefest tree lighting ceremony in Story City, Iowa, on the evening of Nov. 25. Excitement intensified during countdown from 10 to 1 before the lights were flipped on. Then the high school choir led the singing of Christmas carols, and guests could warm up with cups of hot chocolate.

Let there be light

In 1914, Story City became one of the first towns in Iowa to display a municipal Christmas tree with electric lights. While many Iowa communities had begun to offer electrical service in the late 1890s and early 1900s, electricity was still a novelty that held the power to fascinate, especially in rural areas.

At that time, electricity was out of reach for thousands of farm families, many of whom wouldn’t receive electrical service until the federal Rural Electrification Act of 1936 brought power to rural America in the late 1930s and into the 1940s.

When Story City harvested its first municipal Christmas tree in town in 1914, local citizens decorated the tree with large, multi-colored lights. The lighting of the tree became a memorable event for a town that had not fully integrated electricity into all homes. A man who was visiting Story City during the Christmas season in 1914 described the tree as “the biggest stunt the town ever pulled off.”

Other communities took note. After Story City celebrated its first lighted Christmas tree, the event attracted newspaper coverage across the Midwest, and the concept of municipal Christmas trees started gaining popularity in small towns across Iowa and beyond.

Story City’s municipal Christmas tree has even reflected noteworthy moments in American history. No municipal Christmas trees were displayed in Story during World War 2 from 1942 to 1944, Feil said. Also, there was no tree in 1973, and no street ornaments were lit that year, due to the nation’s energy crisis.

Nothing caused more consternation, however, than a decision in 1948 to place a decorative Santa and sleigh with four horses from the town’s iconic carousel at intersection of Broad Street and Pennsylvania Avenue instead of a tree. It didn’t go over well, Feil said. “People like the tree.”

Today, many community members, including Mayor Mike Jensen, have helped make sure Story City has a municipal Christmas tree each year. Since it can be a little difficult to find trees that are right for the municipal tree, community leaders have begun planting evergreens near the soccer fields in the northwest part of Story City, said Huff, who noted that Story City is a member of Trees Forever. These trees will help ensure this beloved tradition lives on.

“From the first tree in 1914 to our current tree, I love the feeling of community our municipal Christmas tree continues to bring each year,” Feil said.

The municipal Christmas tree is unique feature of Exira, Iowa, population 840, which is also known for its 4th of July celebration. “It’s a proud tradition we want to keep around for years to come,” says the city clerk.

Christmas tree helps define Exira

On the other side of the state in Exira, population 840, local residents also cherish the tradition of a municipal Christmas tree that stands tall in an intersection downtown near the town square.

“We’ve had a tree each Christmas for many years,” said Lexi Christensen, Exira’s city clerk. “A lot of people compliment us on this tradition.”

This year’s tree, which was donated by Lana Wiges of Hamlin, was set up the Saturday after Thanksgiving. The tree was officially lit when Santa Claus came to town during the first weekend in December. Has anyone ever crashed into the holiday icon? “Fortunately not,” Christensen said.

As part of the tree lighting celebration, guests enjoyed soup and homemade treats at the local recreation center, while the Exira Community Club collected food and toys to donate to local families in need. “The Christmas tree is unique feature of Exira,” said Christensen, who added that Exira is also known for its 4th of July celebration. “It’s a proud tradition we want to keep around for years to come.”

Remsen revives Christmas tree tradition

Municipal Christmas trees used to be a much more common sight in small Iowa towns, but the tradition faded away in many communities due to the work involved, declining populations and other factors. To Tammy Maaff-Portz, it was a tradition worth reviving in her hometown of Remsen, population 1,663.

“I’d say the tradition had died out by the mid-1960s, but a group of us wanted to bring back an old-fashioned Christmas with a tree in the middle of the road. We made it happen in 2003 and have been carrying on this tradition ever since.”

This year’s municipal Christmas tree stands about 30 feet tall on Main Street and is covered with an array of oversized green and red ornaments and approximately 3,000 lights, including a lighted star on top. The massive tree sits in a permanent hole dug into the street downtown and is held in place with a support system designed for this purpose. The hole in the street is covered with a steel plate the rest of the year.

The lighting of the municipal Christmas tree, which took place the first Monday evening in December, started with a blessing of the tree by local religious leaders. Then Santa arrived on a vintage fire truck and lit the tree before heading to the Remsen Heritage Museum, where children could share their wish list with him and receive a candy cane.

Remsen’s businesses stayed open that evening until about 8 p.m. Carolers walked from shop to shop, singing songs of the season, while visitors enjoyed horse-drawn wagon rides as sleigh bells rang throughout Main Street. Children took advantage of Kids’ Korner, where they could shop for gifts for their family and either wrap the presents themselves or get a little help from the business owners.

“Living windows” in local stores have also become a popular part of the celebration. This year, members of the St. Mary’s boys’ basketball team were at Schorg’s Custom Cabinetry, where visitors could visit with them while decorating their own Christmas cookies.

“All these events are free and open to the public,” said Maaff-Portz, who owns Furnishings on Second At Muller’s. “People of all ages love it.”

Remsen’s municipal Christmas tree stays lit all through the night, every night, until the tree is taken down during the first few weeks of January. Maaff-Portz is already looking forward to a gala event in a few years to celebrate the 15th anniversary of the municipal Christmas tree’s triumphant return to Remsen. “It’s definitely a community effort. We want to make this a family and community tradition as long as we can.”

Christmas Trees Thrive in Iowa

The modern Christmas tree is believed to have originated in Germany in the 16th century. Here are some other Christmas tree facts from the Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship:

- Iowa has more than 100 Christmas tree farms in all parts of the state.

- These farms devote more than 1,500 acres to Christmas tree production in Iowa and harvest approximately 39,500 Christmas trees each year.

- It takes 6 to 12 years to grow a Christmas tree before it is ready to be sold.

- Christmas tree farms in Iowa are part of a $1 million industry that contribute to the state’s economy.

*This article first appeared in Farm News, December 2016

Want more Iowa culture and history? Check out my top-selling “Calhoun County” book, which showcases the history of small-town and rural Iowa, as well as my “Culinary History of Iowa” book from The History Press. Order your signed copy today!

P.S. Thanks for joining me. I’m glad you’re here.

@Copyright 2016 Darcy Maulsby & Co.

Very Veggie: Iowan’s Farm-Fresh Recipes Offer Guilt-Free Eating

For a guy who didn’t care for vegetables as a kid, Adam Nockels has come a long ways. Now he runs Iowa’s Raccoon Ridge Farm, which specializes in an array of naturally-grown produce.

“My foodie friends in college, including one who is a gardener, got me interested in fresh foods and new flavors,” said Nockels, who was born in Lake City but grew up on military bases before returning to the Lake City area.

Food production also appealed to Nockels, a U.S. Air Force veteran who used the G.I. Bill to attend Iowa State University, where he earned his biology degree in 2010. After completing an internship at Turtle Farm near Granger, where he learned about vegetable production and community supported agriculture (CSA), Nockels knew he wanted to work in production agriculture. When he proposed the idea of starting a farm on the land his family owns between Lake City and Auburn, his grandparents Dennis and Sheila Moulds liked the idea.

“My Grandma Sheila and my mom, Debby, have green thumbs,” said Nockels, who has 10 acres in Raccoon Ridge Farm, which includes 2.5 to 3 acres of vegetables grown with organic practices. “I also like working outdoors and growing healthy food for people.”

Nockels grows a wide variety of crops, including green beans, spinach, lettuce, radishes, strawberries, kale, herbs, squash, peas, potatoes, beets, heirloom tomatoes and more, which he sells at the Lake City Farmers Market and through his weekly CSA deliveries in Lake City, Rockwell City and Carroll. Nockels’ favorite heirloom tomato is the Cherokee Purple Tomato, a flavorful variety that was reportedly gifted to a farmer in Tennessee in the 1890s from Cherokee natives. “Nothing is better than an heirloom tomato,” Nockels said. “For me, it’s either slice, salt and go, or use the tomato in a BLT sandwich.”

Nockels’ weekly newsletters for CSA customers include a list of produce supplied that week, brief descriptions of the unique items in the box, tips for storing the produce, recipes and seasonal cooking tips such as how to roast chile peppers. Some of Nockels most popular items are his green beans. In 2015, the sandy, loamy soils of Raccoon Ridge Farm produced almost 450 pounds of green beans, so full-share holders received roughly 23 pounds of green beans each.

Nockels enjoys experimenting with new recipes, as well as relying on tried-and-true family recipes, to showcase the bounty of the harvest. “When good food is prepared properly, it tastes better. This is guilt-free eating.”

Savor more of Iowa and its food stories, history and more

Want more fun Iowa food stories and recipes? Sign up today for my blog updates and free e-newsletter, or click on the “Subscribe to newsletter” button at the top of my blog homepage.

You can also order my “Calhoun County” Iowa history book, postcards made from my favorite photos of rural Iowa and more at my online store. Thanks for visiting!

Roasted Beet Salad with Goat Cheese

1 / 4 cup balsamic vinegar

3 tablespoons shallots, thinly sliced

1 tablespoon honey

1/ 3 cup extra-virgin olive oil

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

6 medium beets, cooked and quartered

6 cups fresh greens (spinach, lettuce, arugula, etc.)

1 / 2 cup walnuts, toasted, coarsely chopped

3 ounces soft fresh goat cheese, coarsely crumbled

Line a baking sheet with tinfoil. Preheat oven to 450 degrees

Whisk the vinegar, shallots and honey in a medium bowl to blend. Gradually whisk in the olive oil. Season the vinaigrette to taste with salt and pepper. Toss the beets in a small bowl with enough dressing to coat. Place the beets on the prepared baking sheet, and roast until the beets are slightly caramelized, stirring occasionally, about 12 minutes. Set aside and cool.

Toss the greens and walnuts in a large bowl with enough vinaigrette to coat. Season the salad to taste with salt and pepper. Mound the salad atop four plates. Arrange beets around the salad. Sprinkle with goat cheese. Serve.

Radish Toast with Sesame-Ginger Butter

4 tablespoons butter, room temperature

3 tablespoons minced chives, divided

1 tablespoon toasted sesame seeds

3 / 4 teaspoon grated peeled fresh ginger

1 / 4 teaspoon Asian sesame oil

16 1 / 4-inch-thick baguette slices, lightly toasted

10 radishes, thinly sliced

Mix butter, 2 tablespoons chives, sesame seeds, ginger and sesame oil in small bowl; season with salt and pepper. Spread butter mixture over each bread slice. Top with radishes, overlapping slightly. Sprinkle with remaining chives.

Spinach Quiche

1 tablespoon butter

2 spring onions, minced

2 bunches spinach, thick stems removed and leaves roughly chopped

Coarse salt and ground pepper

4 ounces Gruyere or Swiss cheese, grated (about 1 cup)

1 frozen pie crust

4 large eggs

1 1 / 2 cups half-and-half

Dash of ground nutmeg

1 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon pepper

Preheat oven to 350 degrees, with racks set in upper and lower thirds. In a large skillet, heat butter over medium. Add spring onions, and cook, stirring occasionally, until softened, 1 to 2 minutes. Add as much spinach to skillet as will fit; season with salt and pepper, and toss, adding more spinach as room becomes available, until wilted, 2 to 3 minutes.

Transfer spinach mixture to a colander. Press firmly with the back of a spoon to squeeze out as much liquid as possible. Sprinkle cheese onto crust. Spread spinach mixture over shredded cheese.

In a large bowl, whisk together eggs, half-and-half, nutmeg, 1 teaspoon salt and 1 teaspoon pepper. Pour egg mixture into crust.

Bake until center of quiche is just set, 55 to 60 minutes. Let quiche stand 15 minutes before serving.

Cover and refrigerate leftovers up to 1 day. Reheat at 350 degrees until warm in the center, 30 to 40 minutes.

Easy Kale Chips

Preheat oven to 350 degrees. Remove large central stem from kale leaves and tear into chip sized pieces. Drizzle with olive oil and add a sprinkle of salt or seasoned salt. Bake in the oven for 10-15 minutes until leaves edges are brown but not burnt.

Peas and New Potatoes

1 pound new potatoes

1 cup shelled peas

1 tablespoon butter

1 tablespoon flour

Salt and pepper to taste

1 cup milk or half & half

Bring a large pot of water to a boil over high heat. Boil potatoes for 15 to 20 minutes, until tender. Drain.

In a medium saucepan, bring 1 cup water to a boil. Simmer peas in boiling water for 6 to 7 minutes, or until tender (do not overcook). Drain.

Using the same saucepan, melt butter over medium heat. Stir in flour to make a thick paste; gradually whisk in milk, stirring constantly until slightly thickened. Season with salt and pepper to taste. Add potatoes and peas to the sauce; simmer for about 5 minutes, stirring often. Serve immediately.

Crisp Tuna-Cabbage Salad

One 5-ounce can tuna, drained

2 cups finely chopped green or red cabbage, from about 4 ounces or 1 / 4 of a small head of cabbage

1 tablespoon mayonnaise

3 tablespoons plain Greek yogurt

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

Shred the tuna with a fork and mix thoroughly with the cabbage. Stir in mayonnaise and yogurt. Add salt and pepper to taste. Eat immediately, or refrigerate for up to two days. Makes two 1-cup servings.

Basil Pesto

1-2 cups fresh basil leaves

2-4 cloves of garlic

3 / 4 cup good olive oil

1 / 2 cup grated Parmesan cheese

1 / 4 cup pine nuts or walnuts (opt.)

Put basil in blender or food processor. Add garlic, and blend, adding olive oil slowly. Add Parmesan and pine nuts. Blend all into a thick sauce.

This is good over any hot pastas. It can be also added to salad dressing, 1 tablespoon at a time, used as a spread for tomatoes, on crackers, etc. Pesto can also be frozen in small container for use later.

Green Bean and Pasta Salad

4 ounces penne pasta, uncooked (1 1/4 cups)

4 ounces green beans, halved crosswise (about 1 cup)

1 cup canned red or kidney beans, rinsed

1/4 cup chopped fresh flat-leaf parsley

2 tablespoons grated Parmesan (2 ounces)

2 tablespoons olive oil

2 tablespoons fresh lemon juice

Kosher salt and black pepper

Cook the pasta according to the package directions, adding the green beans during the last 3 minutes of cooking. Drain and run under cold water to cool.

Toss the cooled pasta and green beans with the red beans, parsley, Parmesan cheese, olive oil, lemon juice, 1 / 2 teaspoon kosher salt, and 1 / 4 teaspoon black pepper. Divide the salad between two containers and refrigerate for up to one day.

Iowa’s Vigilante Crime Fighters of the 1920s and 1930s

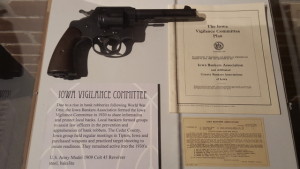

Who were these guys? It’s a question I couldn’t get out of my mind after I discovered a black-and-white image in the Calhoun County Museum in Rockwell City that showed a group of well-dressed men in front of the Calhoun County Courthouse. The only identification on the image, which appeared to be from the late 1920s or early 1930s, were the words “Calhoun County Vigilantes,” along with some long-forgotten names of men I suspect were mayors and other leaders in local towns around the county.

A recent trip to the fascinating “Ain’t Misbehavin:’ The World of the Gangster” exhibit at the Hoover Presidential Library and Museum helped me piece together some potential clues about the story behind this photo.

While bank robbers and swindlers are as old as the banking industry itself, crime sprees shifted into high gear during the early twentieth century. As early as 1912, the Iowa Bankers Association (IBA) decried the “epidemic” of bank burglaries sweeping the state. This proved to be only an inkling of what lay ahead, however. By 1920, burglaries and holdups had increased so dramatically that new protective measures had to be taken.

This 2016 display in the “Ain’t Misbehavin:’ The World of the Gangster” exhibit at the Hoover Presidential Library and Museum in West Branch, Iowa, explains more about vigilantes and the role of the Iowa Bankers Association.had increased so dramatically that new protective measures had to be taken.

Although the Iowa Bankers Association (IBA) had previously employed the services of the Pinkerton Detective Agency and the W. J. Burns Detective Agency, the IBA formed Vigilante Committees in the early 1920s to fight the crime wave. In 1921, IBA helped organize 99 county associations and a Vigilance Committee in nearly every city and town in the state to help protect Iowa’s banks.

Vigilantes attracted international attention

The system was a modern reincarnation of the vigilante groups who fought back against horse thieving and cattle rustling during the days of the pioneers. In Iowa, each Vigilance Committee consisted of at least four men in every town where there was a bank. Each committee member was appointed as a deputy sheriff by the county sheriff. In addition, the banks of each county subscribed to at least a $1,000 reward for the apprehension and conviction of bank burglars, plus smaller rewards for telephone operators who helped in the process.

Arrangements were later made with the U.S. War Department so officers in each of Iowa’s County Bankers Associations could purchase guns and ammunition for the members of their Vigilante Committees. The Vigilance Committees were prepared for—and frequently engaged in—gunfights with criminals. At one time, there were 4,303 vigilantes covering 881 banking towns in 84 Iowa counties. “The time of easy dough for the bank bandit has passed,” noted a financial publication that commented on the plan.

Thanks to this system, the bank theft crime wave that had swept Iowa was broken. While losses from bank burglaries totaled more than $225,000 in 1920-1921, more than 100 bank bandits were apprehended from 1920 to 1925. “The plan was such a success that rates for bank burglary and bank insurance in Iowa were dropped to $1 per thousand, while in other states the rates ranged from $4 per thousand in Missouri to $10 per thousand in Oklahoma,” noted Howard E. Bell in his book, “A History of the Iowa Bankers Association.”

Insurance companies across the United States quickly adopted the Iowa Vigilance Committee Plan. A 10 percent discount for both night burglary and daylight holdup insurance rates was automatically granted to banks in any county in the United States that maintained Vigilance Committees.

Iowa’s Vigilance Committee Plan continued to be of national interest for a number of years and generated coverage in a number of magazines and periodicals. As late as 1930, the IBA received an interview request from a publication in Paris, France, that wanted to feature the Vigilance Committee Plan.

IBA takes to the airwaves

Though the vigilantes helped curb crime in the 1920s and early 1930s, the IBA also initiated a low-wave police radio system to bolster its crime prevention efforts. While Des Moines radio station WHO had broadcast news of bank robberies (when requested by the IBA) as early as 1924, it became clear that a radio station devoted solely to police information must be established.

To connect local law enforcement officers with the Iowa Bureau of Criminal Investigation by radio, the IBA purchased a transmitter that was installed in February of 1932 in the organization’s headquarters in the Liberty Building in Des Moines. After the system was tested carefully, station KGHO began regular operations on May 15, 1933.

Later, four other radio stations in Storm Lake, Atlantic, Fairfield and Waterloo (subsequently moved to Cedar Falls) commenced operations to allowed prompt contact with county sheriffs’ offices throughout Iowa. While the IBA transferred the operation of its radio station in 1937 to the State of Iowa and the organization sold its radio equipment, the IBA’s leadership in radio communication helped initiate Iowa’s permanent, statewide police radio system.

Couldn’t resist getting in on the action at the “Ain’t Misbehavin:’ The World of the Gangster” exhibit at the Hoover Presidential Library and Museum in West Branch, Iowa!

Although radio communication lessened the need for Vigilance Committees, the groups continued to function. The rewards that had been offered by various County Associations were rescinded around 1938, however, as the number of bank holdups and burglaries decreased substantially. As new state crime prevention agencies developed, the suggestion was made to abolish the Vigilance Committees, so banks would no longer have to assume the expense of maintaining the committees. Nevertheless, there were 216 vigilantes who remained active in a number of counties across Iowa as late as 1949.

Although the vigilantes and IBA radio stations are long gone, their legacy remains an intriguing part of Iowa history, including right here in Calhoun County.

Explore more rural Iowa history

Like what you’ve seen here? Sign up today for my blog updates and free e-newsletter, or click on the “Subscribe to newsletter” button at the top of my blog homepage.

Want to discover more stories and pictures that showcase the unique history of small-town and rural Iowa? Perhaps you’d like a taste of Iowa’s culture and favorite recipes. Check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa” book from The History Press and “Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing, and order your signed copies today.

Mayday, Mayday—The Lost History of May Poles and May Baskets in Iowa

Remember the fun, colorful tradition of creating homemade May baskets? (I do.) If you’re a certain age, you may even remember dancing around the May pole. (I don’t). All were once beloved rites of spring here in Iowa and across America.

In many Midwestern communities, May Day celebrations were a highlight of the year. As I researched my book “Calhoun County,” which showcases the history of small-town and rural Iowa through the eyes of those who lived it, I came across a unique picture. Thelma Basler, a member of the senior class of 1935, was elected May Queen by the Lohrville High School student body. In addition to voting for the May Queen

Lohrville High School May Queen, Thelma Basler, 1930s, Lohrville, Iowa

, students decorated the school flagpole in honor of May Day and delivered May baskets to friends.

While these May 1 customs have largely faded from American pop culture, they still endure in pockets of Iowa and beyond, where some of my friends’ children still enjoy making May baskets filled with treats. I started thinking—where did these May Day traditions come from? A little research hinted at something less wholesome than childhood craft projects and school celebrations.

Taming a raucous rite of spring

May pole dancing, for example, dates back to ancient pagan cultures in Europe. Each spring, people would erect a May pole, often of cedar or birch, and dance around it, typically weaving colorful ribbons around the pole as they went, to ensure a fruitful planting season.

An obvious phallic symbol, a May pole was strongly associated with fertility. After the European continent became Christianized, the more raucous elements of May Day celebrations were toned down, but the May pole dance and May baskets survived in a more G-rated form. These customs were carried to America, where they endured well into the twentieth century.

May Day memories from small-town Iowa

In my home town of Lake City, Iowa, Jolene Schleisman recalls weaving ribbons around a May pole in the gymnasium/lunchroom at Lincoln Elementary School in the 1960s. This spring ritual had ended by the time I attended Lincoln Elementary in the 1980s, although I did take square-dancing lessons in

Homemade May baskets created in Lake City, Iowa

music class, a tradition that has now gone the way of the May pole.

During my time at Lincoln Elementary, I did get to experience the joy of making May baskets filled with candies and popcorn to give to friends and family. In the 2015 article “A Forgotten Tradition: May Basket Day,” NPR explained the phenomenon this way:

“As the month of April rolled to an end, people would begin gathering flowers and candies and other goodies to put in May baskets to hang on the doors of friends, neighbors and loved ones on May 1. In some communities, hanging a May basket on someone’s door was a chance to express romantic interest. If a basket-hanger was espied by the recipient, the recipient would give chase and try to steal a kiss from the basket-hanger.”

In Lake City, homemade May baskets became a fundraiser for the ladies of the Presbyterian Church in the mid-twentieth century. Church members including Fanny Howell, principal of Lake City High School from 1928 to 1935, made May baskets out of small paper milk cartons (washed and sanitized with bleach). The ladies decorated each May basket with colorful crepe paper and attached pipe cleaners for handles.

The cheerful baskets were displayed in the front window of McIntyre Furniture store on Center Street, where the smaller baskets could be purchased for a penny apiece. Buyers could then fill the baskets with the treats of their choice and deliver them to friends around town.

Long gone are the penny May baskets, McIntyre Furniture, Fanny Howell and many of the traditions that once defined May 1 in communities across Iowa and beyond. In one respect, however, I’m glad that some major company has not rediscovered May Day, only to mar its simplicity with commercial baskets, cards and trinkets. There’s still something to be said for simplicity and tradition.

Savor more Iowa food history

Want more fun Iowa food stories and recipes? Sign up today for my blog updates and free e-newsletter, or click on the “Subscribe to newsletter” button at the top of my blog homepage.

Check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa” book from The History Press, and order your signed copy today. You can also order my “Calhoun County” Iowa history book, postcards made from my favorite photos of rural Iowa and more at my online store. Thanks for visiting!